Two stories about trees floating in upright position appeared in the media this month: one related to something that has long been a traditional feature of park landscaping, the other as part of a climate change awareness project. They made me think of an earlier example.

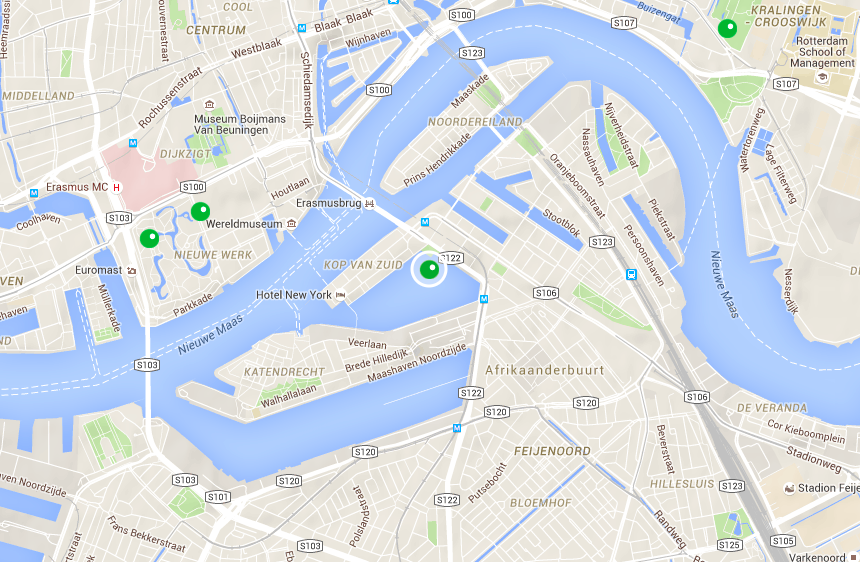

The traditional story comes from Georgia (see this BBC coverage), where a new park is laid out by former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili. To give his park more ‘body’, mature trees are imported from elsewhere -nothing new in landscape architecture. One of these trees, a Tulip tree of around 100 years old, was uprooted in the west of the country. Its transport by boat over the waters of the Black Sea provided images such as this:

A 100 year-old Tulip tree is transported over the waters of the Black Sea.

Closer to home, Rotterdam saw the eh… ceremonial launch of a Bobbing Forest in the former harbour basin Rijnhaven. This project by Rotterdam art production collective Mothership is inspired by and a cooperation with Columbian artist Jorge Bakker. It takes a somewhat light-hearted approach to problems associated with climate change: the predicted rise of sea levels and its possible consequences for low lying land -like Rotterdam and much of the Netherlands. Even in today’s storm, the trees seem to cope well with the conditions.

The Bobbing Forest in the Rijnhaven. (photos: HvdE).

Pliny the Elder

Both stories made me think of what Pliny the Elder wrote about this part of the world. At the height of their expansion into Northwestern Europe, the Romans managed to occupy the southern half of what is now the Netherlands. The larger rivers running towards the North Sea formed a natural boundary along which the border (the ‘limes‘) was formed. The river Rhine was also an important trade route. Peoples living to the north were hostile to the Roman occupation, and they often successfully defended their territory against Roman attacks -in which Pliny himself was involved. To defend themselves against attacks from the north, the Romans created army camps along the border, and they had ships patrolling the rivers.

Pliny notes that at several occasions, Roman sailors thought they were being attacked by enormous enemy ships. In reality, their rigging was wrecked by mature trees, standing on islands floating down the river. It must have been a majestic sight to see these trees float towards and onto the sea, comparable with the Tulip tree transport on the Black Sea.

Like the Roman attempts to occupy new territory, the Georgian ‘tree grab’ leads to protests from the locals, who may not be satisfied with the promised replanting of trees for compensation. Collecting mature trees from elsewhere for the benefit of a few individuals is not as acceptable as it seems to have been during the 19th and early 20th centuries, when this was fairly common practice among estate owners and landscape architects. That ‘climate’ seems to have also changed.

2000 years

The Rotterdam project is planned to run between five and ten years, but I think that period should be expanded, provided the elm trees can reach some form of maturity in this environment. We could create a modern version of these ancient floating forested islands by cutting loose bobbing forest in a few decades from now. For example in 2047, exactly two millennia after Pliny supposedly roamed these parts and must have heard his soldiers tell those stories.

I like to think this would both commemorate an important period of our history, and be a strong reminder that climate change played a significant role in the decline and fall of the Roman empire.

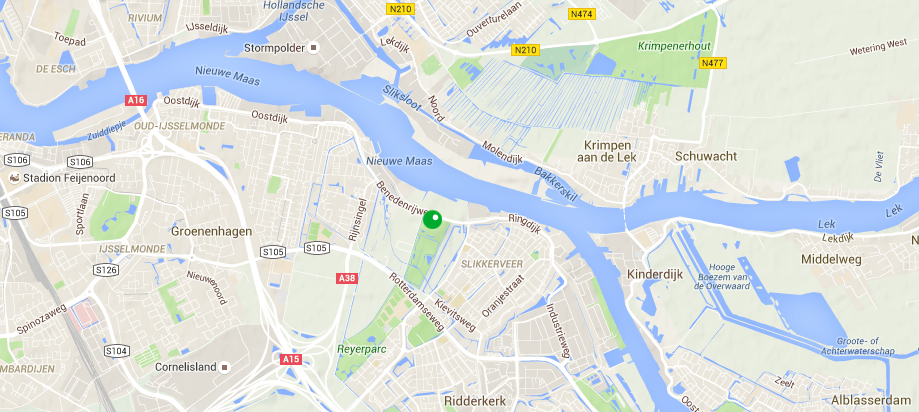

Location of the Bobbing Forest project in the Rijnhaven in Rotterdam.

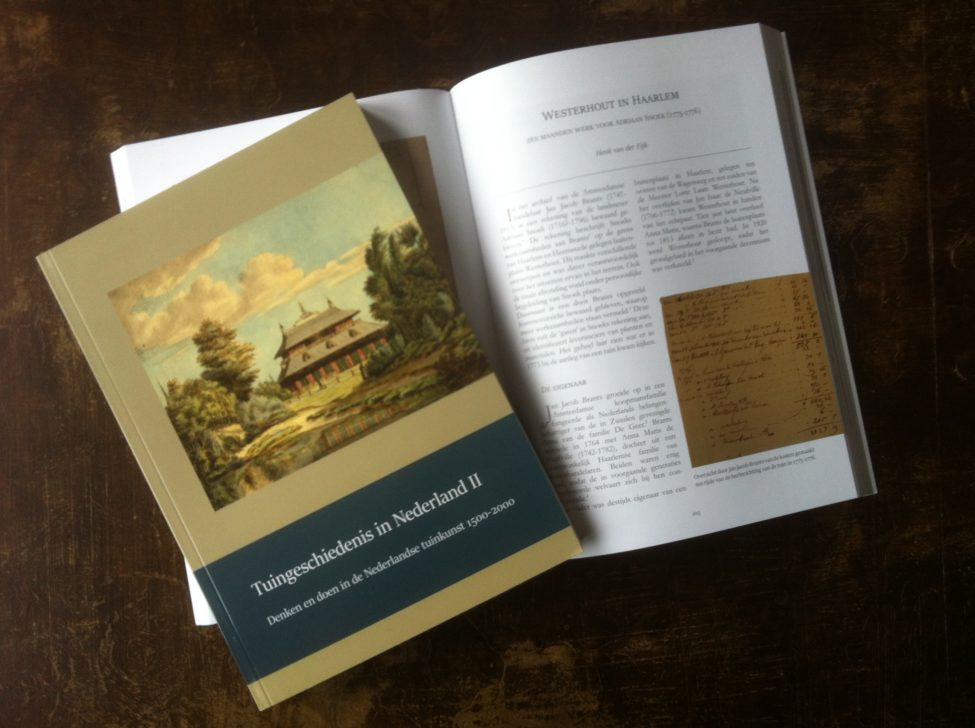

The 18th century garden of Westerhout, however, has been completely forgotten. That is mainly due to the fact that roughly a century ago the garden has been fully redeveloped, and because plans or descriptions of the garden hardly exist. In this country that particular combination means: no research whatsoever is done.

The 18th century garden of Westerhout, however, has been completely forgotten. That is mainly due to the fact that roughly a century ago the garden has been fully redeveloped, and because plans or descriptions of the garden hardly exist. In this country that particular combination means: no research whatsoever is done.

Ervan uitgaande dat hier geen sprake is van een anomalie in het beeld, wijst een ruwe schatting mijnerzijds uit dat de piramide van Huys ten Donck een basis had van 5 à 10 meter -afhankelijk van de vraag op welke manier de AHN2-gegevens moeten worden geïnterpreteerd.

Ervan uitgaande dat hier geen sprake is van een anomalie in het beeld, wijst een ruwe schatting mijnerzijds uit dat de piramide van Huys ten Donck een basis had van 5 à 10 meter -afhankelijk van de vraag op welke manier de AHN2-gegevens moeten worden geïnterpreteerd.

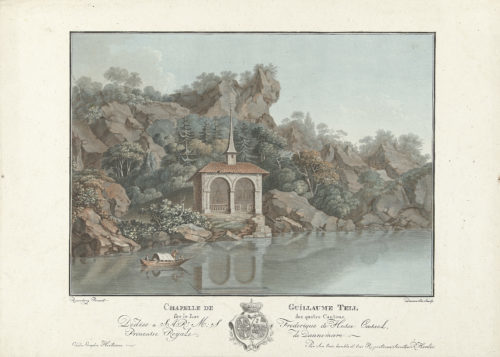

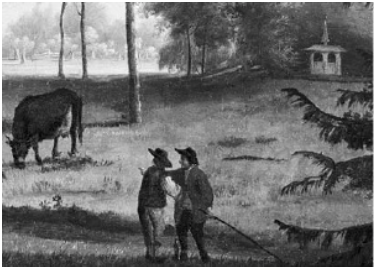

In het park van Huys ten Donck stond ooit een tuingebouw, dat wel werd aangeduid als ‘het huisje van Wilhelm Tell’. De bouwdatum ervan is niet bekend, volgens Tromp ‘waarschijnlijk van ca. 1800.'

In het park van Huys ten Donck stond ooit een tuingebouw, dat wel werd aangeduid als ‘het huisje van Wilhelm Tell’. De bouwdatum ervan is niet bekend, volgens Tromp ‘waarschijnlijk van ca. 1800.'