In earlier posts I’ve considered some of the ‘continental sources’ who may have been relevant to Audley End owner John Griffin Griffin in purchasing 3,000 alders from Rotterdam (part 1), and established that alders were frequently shipped from Rotterdam to Great Yarmouth (part 2). In this last part I’ll be talking money and propagation methods.

Propagation

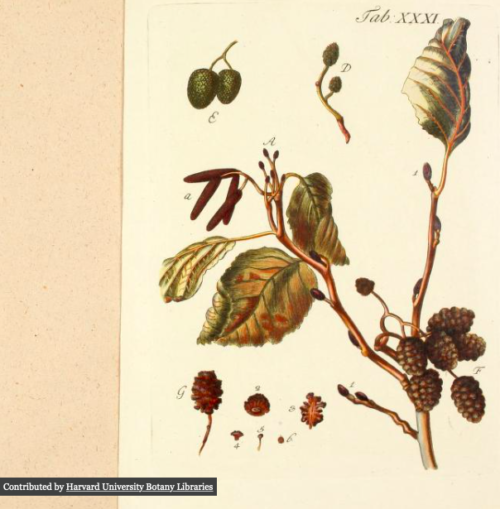

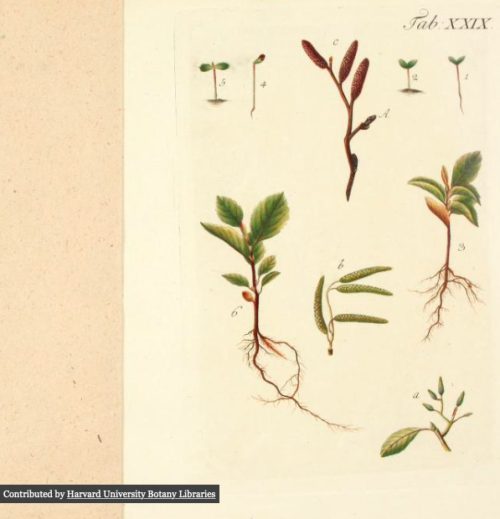

The alder, seen here up close in different stages on engravings by Adam Wolfgang Winterschmidt,1Both etchings by him shown here are from Carl Christoph Oelenhafen von Schöllenbach, Abbildung der wilden Bäume, Stauden und Buschgewächse, welche nicht nur mit Farben nach der Natur vorgestellet, sondern auch … kurz und gründlich beschrieben werden (Nürnberg 1767), vol. 1, p129 and related tables (via BioDiversity Library). has always been an easy plant to propagate, provided it is allowed to grow in very wet conditions. Philip Miller presented two methods in the 1754 edition of his Gardener’s Dictionary: by layering and subsequent replanting a year later; and in situ by simply thrusting an alder stake deep into moist and loose soil.2Philip Miller, Gardener’s Dictionary (etc.), edited and improved version (London 1754), Alnus.

Despite this simplicity, exporting alders overseas (meanwhile subjecting them to danger of loss and to extra costs of transport, packaging and customs charges) appears to have been a profitable business case for Dutch nurserymen and their clients.

This profit may have rooted in a different propagation method than the ones described by Miller, one from the realm of agriculture, not horticulture. An edition of the Dutch translation (published in 1778) of the widely used, adapted and translated early 18th century Dictionnaire Economique by Noël Chomel, provides this alternative method besides Miller’s. Farmers working on peaty soils sowed alder seed on well prepared soil, and just let them grow for three to four years.3Noel Chomel, second enhanced edition by J.A. de Chalmot, Algemeen huishoudelijk-, natuur-, zedekundig- en konst-woordenboek, vervattende veele middelen om zijn goed te vermeerderen en zijne gezondheid te behouden, met verscheidene wisse en beproefde middelen voor een groot getal van ziektens en schoone geheimen om tot een hoogen en gelukkigen ouderdom te geraken (Leiden/Leeuwarden 1778), vol. 2, p625. The first edition of the Dutch translation was published in 1743, the first Dutch edition of the enhanced edition was published between 1768-1777. Apart from some weeding and thinning to give each plant the space it needs, this was a labour extensive method. After three or four years the whole field was harvested at once. Large parts of the western half of the Dutch republic consist of such peaty soils, and we’ll see later that this method was indeed used in the Netherlands. Unlike the original French version and the English translation I have seen, this Dutch version of Chomel tells us farmers brought an abundance of their alders to the markets each Spring:

Het zaaijen en kweeken der elsen is in onze Provintien veel het werk van de veen- en woud-boeren, die de jonge boomen vervolgens in de voorjaarstijd in menigte ter markt brengen, om dat ze niet alleen in de laage veen- en woud-plaatzen zeer wel groeijen en schielijk aangroeijen, maar ook in Nederland veel geplant worden.

Sizes and prices

A source closer to home, dealing with the transformation of waterlogged land into arable soil by using alders as a first crop, underscores that this propagation method was used in the Netherlands. But it also provides valuable information about the end product. Published in 1784 on behalf of the Society for Agricultural Improvement in Amsterdam, Johannes Evenbly described the results of this method tested out four decades earlier, in the 1740s.4Johannes Evenbly, ‘Bericht wegens verscheide proeven genomen tot het weer in stand brengen van nietswaardige landeryen, aan de Maatschappy van den Landbouw medegedeeld in 1784.’, in: Verhandelingen uitgegeeven door de Maatschappy ter bevordering van den Landbouw te Amsterdam, vijfde deel, eerste stuk (Amsterdam 1788), p69. With respect to the alders, Evenbly describes his experiences of some 40 years earlier (see p68). The sow-and-let-grow method he used didn’t yield a consistent batch of plants of similar shapes and sizes: its primary goal was land improvement at a low cost. Any alders that could be sold after three to four years only helped to minimize expenditure. Harvested alder plants were divided into three categories. The largest and most expensive ones were called Koning-Els, or Voorloop.5‘Els’ is Dutch for alder. Think of King-size, but the alternative name may have been better suited for people living in a republic. ‘Voorloop’ is not or hardly used in modern Dutch, but used to refer to products that were best and/or largest in their class. See Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal, ‘Voorloop’. The smaller category, sold for half the price, was called Middel-Els. There seems to have been no name for the leftovers forming the third category, which were sold for small change.6Evenbly called these Druypelingen, another word that has gone out of use in the Dutch language (but I only saw it mentioned in his work, I haven’t seen other sources confirming this name). Prices were set per batch of 1,000 plants (or per 100 for a smaller number of them).

Confirmation that these agricultural products were actually sold in the nursery trade comes from the archives of an estate in Ridderkerk, not far from Rotterdam. Huys ten Donck (pictured here in 2010) was and is till this day home to the Groeninx van Zoelen family. Nurseryman Jan Janmaat was the main supplier of plants for this estate in the period between 1763 and 1777.7Despite the abundance of material relating to Jan Janmaat in this archive, it is still not clear where his nursery was. In one or two cases he signed a bill with the name Jan Maat. He may have already supplied plants for Huys ten Donck in the period before 1763. During these fourteen years, records show that he supplied Huys ten Donck with just over 30,000 alders of the largest kind, or as he billed them: Voorloop van Elst.8The grand total was 30,079 alders. His ‘Elst’ may have been local dialect for the more common ‘Els’. Over the years he charged between nine and eleven guilders per ‘roughly’ 1,000 alders (‘± duysd’).9It seems these prices were independent from the size of the order, the same price was used for 75 plants and for 1,100 plants. On 18 December 1775, 75 alders were delivered at a rate of 18 stuivers per 100, which translates to ƒ9,- per 1,000. Stadsarchief Rotterdam (SAR), Toegang 30, Archief van het Huys ten Donck, inv.nr 1336. Bill for plant deliveries by Jan Janmaat to Cornelis Groeninx van Zoelen, paid 10 September 1776. I suppose precision was not an issue here.

The Audley End alders

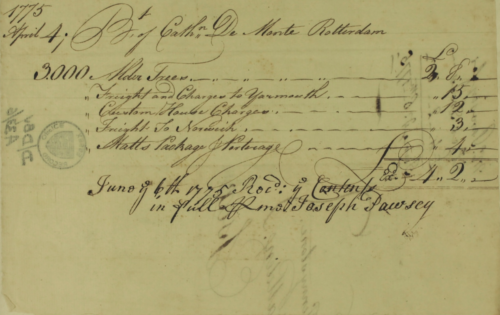

What does this tell us about the alders bought for and delivered to Audley End in the Spring of 1775? Well, we know their price without additional costs: £ 2 8s. for 3,000 alders. Was this a normal price in the Netherlands? And was this a good deal for Audley End?

Janmaat usually sold his Voorloop alders at a price of nine or ten guilders per 1,000 plants, sometimes eleven (always in round numbers). Around the time of the Audley End purchase, prices lingered around the lower end of the range: ƒ9,- on 21 March and 5 September 1774,10SAR, Toegang 30, inv.nr 1335. Bill for plant deliveries by Jan Janmaat to Cornelis Groeninx van Zoelen, paid 3 January 1775 (1,100 alders at both deliveries). ƒ10,- on 27 March 1775,11SAR, Toegang 30, inv.nr 1335. Bill for plant deliveries by Jan Janmaat to Cornelis Groeninx van Zoelen, paid 9 September 1775 (1,300 alders). and back to ƒ9,- in 1777.12SAR, Toegang 30, inv.nr 1337. Bill for plant deliveries by Jan Janmaat to Cornelis Groeninx van Zoelen, paid 9 September 1777 (400 alders delivered on 8 April 1777 at 18 stuivers per 100). The official pound-guilder exchange rate at the Amsterdam exchange (Wisselbank) was relatively low at ƒ10,12 per pound in 1770, and at a relative high of ƒ10,71 in 1780.13As shown in a table using decimals published in W.L. Korthals Altes, De geschiedenis van de Gulden; Van Pond Hollands tot Euro (Amsterdam 2001), p65. Of course exchange rates fluctuated throughout the decade: the rate was at around ƒ10,71 per pound in March 1775, dropping to ƒ10,59 in April of that year.14N.W. Posthumus, Nederlandsche Prijsgeschiedenis, Deel I: Goederenprijzen op de beurs van Amsterdam 1585-1914; Wisselkoersen te Amsterdam 1609-1914 (Leiden 1943), p606.

Following Postumus, I’m calculating in decimals here. In Amsterdam the value of the pound Sterling was traditionally calculated against the value of the pound Flemish (pond Vlaams). This currency, like the pound Sterling, was divided in 20 schellingen (Postumus, p.LVI). Its exchange rate against the guilder was stable over the course of the 18th century and up till 1795 was consistently valued at ƒ6,- (Postumus, p.LVII).

In March 1775, 1 pound Sterling was worth 35,7 schellingen, which means 1 pound Sterling was worth 1,785 pound Flemish (35,7 divided by 20). Multiplied by 6 gives a value in guilders of ƒ10,71 per 1 pound Sterling. In April 1775, the number of schellingen per 1 pound Sterling had dropped to 35,3 (=1,765 pound Flemish, or ƒ10,59). Given these exchange rates, the initial purchase price of £ 2 8s. roughly translates into an approximate ƒ25,5 for 3,000 plants, or ƒ8,5 per 1,000 alders.15If my calculations are right, £2 8s. is 2,4 pounds in decimals. Multiplied by the exchange rates used in Amsterdam, the total price in guilders ranges from ƒ25,44 to ƒ25,70 for 3,000 plants. This is just under the lowest price charged by Janmaat at Huys ten Donck. Of course Jan Janmaat charged retail prices and he would have been a bad businessman if he didn’t include transportation costs.

The extra costs of buying his plants overseas (£ 1 14s.) added a significant amount to Griffin’s otherwise reasonable purchase price. He ultimately payed just over ƒ6,- extra per 1,000 alders. This means the extra costs amounted to an additional 2/3 of their normal (retail) purchase price in the Netherlands.

To summarise

The De Monte’s (part 1) were not in the business of growing plants and no specific contract to supply alder trees has been found in relation to them. Catherin Mary de Monte was the ultimate beneficiary of this transaction, but she probably has never known, nor cared much for where ‘her’ alder trees went.

Jan Walraad van Welderen is not known at all for his interest in gardening and it’s unlikely he would have been asked by his brother-in-law to arrange for some plants to be sent from his native country.

The scenario that alders were shipped from Rotterdam to Great Yarmouth just because the hinterland of both places made such a shipment worth the effort, seems plausible. In this case a specific order (through Thomas Pennystone) from Audley End must have started the process (part 2).

If a single nurseryman’s prices are anything to go by, it is very likely that John Griffin Griffin bought three to four year old alders, grown from seed as an agricultural crop and brought to the market in Spring. One would expect they were of the best quality available: the Voorloop, or King-size. Griffin would have paid a low to normal price for them for Dutch standards, but given the additional costs it is hard to imagine he couldn’t get a better deal in Britain. It would have been even worse if the plants were not of the highest quality (Evenbly tells us Middel-Els was sold at half the price of Voorloop). From a strictly economical point of view this transaction doesn’t seem to have made much sense, unless there was no alder production capacity at this scale available at all in Britain.

Whether Sir John Griffin Griffin did a good deal mainly depends on what would have been available to him in the local market. Apparently it made sense at the time to get these alders from overseas, but it would be good if there was some more data available from the British Isles to put this purchase into context.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Both etchings by him shown here are from Carl Christoph Oelenhafen von Schöllenbach, Abbildung der wilden Bäume, Stauden und Buschgewächse, welche nicht nur mit Farben nach der Natur vorgestellet, sondern auch … kurz und gründlich beschrieben werden (Nürnberg 1767), vol. 1, p129 and related tables (via BioDiversity Library). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Philip Miller, Gardener’s Dictionary (etc.), edited and improved version (London 1754), Alnus. |

| ↑3 | Noel Chomel, second enhanced edition by J.A. de Chalmot, Algemeen huishoudelijk-, natuur-, zedekundig- en konst-woordenboek, vervattende veele middelen om zijn goed te vermeerderen en zijne gezondheid te behouden, met verscheidene wisse en beproefde middelen voor een groot getal van ziektens en schoone geheimen om tot een hoogen en gelukkigen ouderdom te geraken (Leiden/Leeuwarden 1778), vol. 2, p625. The first edition of the Dutch translation was published in 1743, the first Dutch edition of the enhanced edition was published between 1768-1777. |

| ↑4 | Johannes Evenbly, ‘Bericht wegens verscheide proeven genomen tot het weer in stand brengen van nietswaardige landeryen, aan de Maatschappy van den Landbouw medegedeeld in 1784.’, in: Verhandelingen uitgegeeven door de Maatschappy ter bevordering van den Landbouw te Amsterdam, vijfde deel, eerste stuk (Amsterdam 1788), p69. With respect to the alders, Evenbly describes his experiences of some 40 years earlier (see p68). |

| ↑5 | ‘Els’ is Dutch for alder. Think of King-size, but the alternative name may have been better suited for people living in a republic. ‘Voorloop’ is not or hardly used in modern Dutch, but used to refer to products that were best and/or largest in their class. See Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal, ‘Voorloop’. |

| ↑6 | Evenbly called these Druypelingen, another word that has gone out of use in the Dutch language (but I only saw it mentioned in his work, I haven’t seen other sources confirming this name). |

| ↑7 | Despite the abundance of material relating to Jan Janmaat in this archive, it is still not clear where his nursery was. In one or two cases he signed a bill with the name Jan Maat. He may have already supplied plants for Huys ten Donck in the period before 1763. |

| ↑8 | The grand total was 30,079 alders. His ‘Elst’ may have been local dialect for the more common ‘Els’. |

| ↑9 | It seems these prices were independent from the size of the order, the same price was used for 75 plants and for 1,100 plants. On 18 December 1775, 75 alders were delivered at a rate of 18 stuivers per 100, which translates to ƒ9,- per 1,000. Stadsarchief Rotterdam (SAR), Toegang 30, Archief van het Huys ten Donck, inv.nr 1336. Bill for plant deliveries by Jan Janmaat to Cornelis Groeninx van Zoelen, paid 10 September 1776. |

| ↑10 | SAR, Toegang 30, inv.nr 1335. Bill for plant deliveries by Jan Janmaat to Cornelis Groeninx van Zoelen, paid 3 January 1775 (1,100 alders at both deliveries). |

| ↑11 | SAR, Toegang 30, inv.nr 1335. Bill for plant deliveries by Jan Janmaat to Cornelis Groeninx van Zoelen, paid 9 September 1775 (1,300 alders). |

| ↑12 | SAR, Toegang 30, inv.nr 1337. Bill for plant deliveries by Jan Janmaat to Cornelis Groeninx van Zoelen, paid 9 September 1777 (400 alders delivered on 8 April 1777 at 18 stuivers per 100). |

| ↑13 | As shown in a table using decimals published in W.L. Korthals Altes, De geschiedenis van de Gulden; Van Pond Hollands tot Euro (Amsterdam 2001), p65. |

| ↑14 | N.W. Posthumus, Nederlandsche Prijsgeschiedenis, Deel I: Goederenprijzen op de beurs van Amsterdam 1585-1914; Wisselkoersen te Amsterdam 1609-1914 (Leiden 1943), p606. Following Postumus, I’m calculating in decimals here. In Amsterdam the value of the pound Sterling was traditionally calculated against the value of the pound Flemish (pond Vlaams). This currency, like the pound Sterling, was divided in 20 schellingen (Postumus, p.LVI). Its exchange rate against the guilder was stable over the course of the 18th century and up till 1795 was consistently valued at ƒ6,- (Postumus, p.LVII). In March 1775, 1 pound Sterling was worth 35,7 schellingen, which means 1 pound Sterling was worth 1,785 pound Flemish (35,7 divided by 20). Multiplied by 6 gives a value in guilders of ƒ10,71 per 1 pound Sterling. In April 1775, the number of schellingen per 1 pound Sterling had dropped to 35,3 (=1,765 pound Flemish, or ƒ10,59). |

| ↑15 | If my calculations are right, £2 8s. is 2,4 pounds in decimals. Multiplied by the exchange rates used in Amsterdam, the total price in guilders ranges from ƒ25,44 to ƒ25,70 for 3,000 plants. |