In part 1 of this series I looked at possible ‘continental sources’ John Griffin Griffin may have used to purchase plants in Rotterdam for Audley End in 1775. In this second part I look at the role existing trade routes may have played.

A few days after tragically falling into the hold of his ship in the harbour of Great Yarmouth, captain Walter Phinn died on Tuesday 3 August 1773. An obituary in a newspaper said he had been ‘many years a commander of a vessel in the Rotterdam trade’.1The Ipswich Journal, Saturday 07 August 1773, p2. Via The British Newspaper Archive (£). An announcement in the same newspaper some six years earlier shows how he may have operated.

YARMOUTH, Sept. 12, 1767. THE Ship Friendship, Walter Phinn, Master, will sail for Rotterdam the 13th of September instant : —She will wait there a Fortnight, to take in Goods and Liquors for Norwich, & any other Place in the Counties Norfolk or Suffolk.2The Ipswich Journal, Saturday 12 September 1767, p3. Via The British Newspaper Archive (£).

This advert served as a last call to provide Phinn with goods destined for Rotterdam, or to fill his order book with goods to ship back from there. While London was the main international trading hub in Britain, the trade route between Great Yarmouth and Rotterdam was very busy too.3Rotterdam’s main overseas trading partners were in England, Scotland and Ireland. P.W. Klein, ”Little London’: British merchants in Rotterdam during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’, in: D.C. Coleman & Peter Mathias [eds], Enterprise and History. Essays in honour of Charles Wilson (Cambridge 1984), p116-134. The relative proximity of both harbours and their accessible hinterland enabled a constant flow of goods from one coast to the other. The preserved part of a doorframe (pictured above) from a house at the Haringvliet in Rotterdam, inscribed ‘Norwich and Iarmouth’, shows the importance of England’s east coast for the city.4From the Museum Rotterdam collection in Rotterdam, dated between 1675 and 1700. Apparently market-boats to Norwich and Great Yarmouth left from the quay before this house. Mutual dependency was so strong that even the ongoing 4th Anglo-Dutch War (1780-1784) didn’t stand in the way of Great Yarmouth hosting a Dutch Fair in September 1783.5The timing of this event is remarkable. Many British shipowners in Rotterdam quickly sold their ships at the start of the war because trade under Dutch or British colours had become too dangerous. P.W. Klein (op.cit. in footnote 3) p131. The Norfolk Chronicle wrote that week: ‘(…) Same day near seventy Dutch fishing scoots arrived at Yarmouth quay. To-morrow begins what is called the Dutch fair‘.6Norfolk Chronicle, Saturday 20 September 1783, page 4. Via The British Newspaper Archive (£). This painting of a Dutch fair on the beach at Yarmouth by George Vincent (1796–1831) is dated 1821 and is currently in the collection of Elizabethan House Museum in Great Yarmouth.

The number of British merchants in Rotterdam was large enough for Swedish traveller Bengt Ferrner to remark that most inhabitants spoke English in what the British merchants called ‘Little London’.7Bengt Ferrner, Resa i Europa 1758-1762 (Uppsala 1956), p129. He wrote this on 2 July 1759, the first day of his stay at Rotterdam. Resident Lucretia Lombe was born in Norwich and in 1756 as a widow bought a new house at the north side of the Haringvliet from Robert Partridge jr, a Norwich based merchant whose father had settled in Rotterdam decades earlier.8W.J.L. Poelmans, ‘Monté (de)-Lombe’, in: De Nederlandsche Leeuw, jrg. 42 (1924), columns 154-155. See for some info on Robert Partridge sr: P.W. Klein (op.cit. in footnote 3), pp125 and 129. Given the sizable British merchant community there it is no surprise that teenage Humphry Repton ended up in Rotterdam the following decade.

Walter(s) Phinn

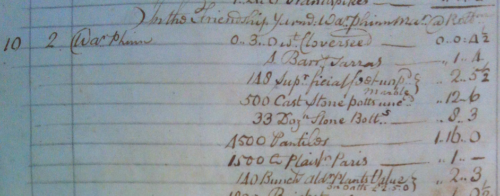

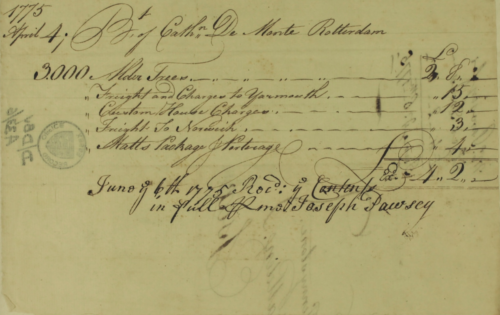

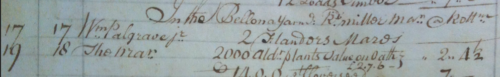

Walter Phinn had been sailing to Rotterdam since at least August 1739, when he was one of three British captains seen sailing off to ‘Jarmouth’ in a matter of days.9Leydse courant, Ao 1739, No 102 (26 August 1739), front page, “NEDERLANDEN.“. Scroll down to the text under the header Rotterdam. Port Books of Great Yarmouth in the period reflect the bustling trade between the two cities.10National Archives, E 190; Exchequer: King’s Remembrancer: Port Books; E190/580/3, ‘Yarmouth, Controller Overseas, Xmas 1774 – Xmas 1775’. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank the team of Conversation Technicians at the NA, who have been very helpful and forthcoming in preparing items pertaining to ‘Yarmouth’ before my visits. In April 1775, two years after his fatal accident, another Walter Phinn (‘Mar @Rottm‘, and probably a son of the first) and his ship called Friendship brought ‘140 Bunch aldr Plants’ from Rotterdam to Great Yarmouth.11National Archives, E 190/580/3 (op.cit. in footnote 10). Phinn arrived on 10 April 1775, six days after the ‘date stamp’ on the bill. A week later captain Robert Miller arrived from Rotterdam with the Bellona, carrying ‘2000 aldr Plants’.12National Archives, E 190/580/3 (op.cit. in footnote 10). His ship arrived on 17 April 1775. Unfortunately it remains unclear whether Phinn already brought enough plants, but both shipments combined must have sufficed to complete the order of ‘3.000 Alder Trees’ for Audley End.13Unfortunately we don’t know how many plants formed a Bunch. Given the similar ‘Value on Oath’ provided for both (£2-5-0 vs £2-7-6), the number of plants may have been the same. But at this point it’s not possible to make an educated guess.

Alder plants as a commodity?

Research in the Port Books in this decade shows that customs officers in Great Yarmouth saw alders coming in regularly. The number of plants arriving during Lady Day- and Midsummer Day quarters varied: from a total of 10.000 plants in 1770 and 1778, down to 1500 in 1772 (none arrived in 1777 and 1779). Besides the captains and boats already mentioned, they were brought in by Richard Miller, captain of the Polly, and Benjamin Thompson, who operated the Norwich Paquet Boat.14From 1776 onwards the records for this customs office became less detailed and only the total numbers of incoming goods per quarter were registered. Ports of origin were reduced to country of origin and the names of ships and captains were not identified anymore.

Newspaper adverts show that Dublin was another regular destination for Dutch alder plants in this decade. One local newspaper in 1775 had a Dublin seedsman announce:

‘Now landing from on board the Cornelia from Rotterdam, by Edw. Bray, Seedsman, on the Merchant’s-quay, near the Old Bridge, Dublin, some Thousands of handsome Dutch Alder Trees, which he will sell reasonable; (…).'15Saunders’s News-Letter of Friday 10 February 1775, p2. Via The British Newspaper Archive (£). There are more examples of these kind of adverts in Saunders’s Newsletter during the decade.

The perhaps surprising conclusion must be that these common plants were often found on board of ships carrying goods via Rotterdam into Britain and Ireland. But the ‘value on oath’ that accompanied these shipments in port books confirms this was not a staple good for which standard import quota were in place – a declaration or estimate of their value was accepted as a basis for taxation.

Did captains Phinn and Miller load these alders knowing they’d sell easily on the other shore? Or were they specifically sent to collect them? We just don’t know for certain.16The Port Books do not provide enough information to directly connect either transport to the sender or receiver on the bill, Pennystone or De Monté. But how feasible is it that a merchant would send live plants overseas without knowing they’d sell at the other side? The Dublin transports were probably initiated by local seedsmen. And looking at the Audley End bill it is likely that at least one of the Great Yarmouth shipments in 1775 was a commission.17Essex Record Office; D/DBy A33/6, Audley End estate, Household and Estate Papers 1775. The address on the back of the bill is partly missing, but it appears to be addressed to Thomas Pennystone in Saffron Walden, at the time apparently steward of Audley End.18The words ‘Pennystone’, ‘/allden’ and ‘Essex’ can still be read. The ships arrived at Great Yarmouth six and thirteen days after the date on the bill. If it was standard practice for Phinn and Miller to wait at Rotterdam for 14 days before sailing back, they could have both brought along a written order from Pennystone on their way to Rotterdam.

Although falling into a larger pattern of trade and shipping routes, this foreign purchase was a deliberate one. Since alders are hardly exotics, the question is: why would Audley End and Dublin seedsmen buy these plants overseas? It may have depended on what exactly they bought.

In 1966, J.D. Williams seemed doubtful whether this had been a good deal for John Griffin Griffin, given the extra costs he incurred for transport, packaging and ‘Custom House charges’.19J.D. Williams, Audley End. The Restoration of 1762 – 1797, Essex Record Office publications, No. 45 (Chelmsford 1966), p46. There is a little bit of information available about Dutch alder prices and sizes. In a third and final part of this series I’ll go into that in more detail.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | The Ipswich Journal, Saturday 07 August 1773, p2. Via The British Newspaper Archive (£). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Ipswich Journal, Saturday 12 September 1767, p3. Via The British Newspaper Archive (£). |

| ↑3 | Rotterdam’s main overseas trading partners were in England, Scotland and Ireland. P.W. Klein, ”Little London’: British merchants in Rotterdam during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’, in: D.C. Coleman & Peter Mathias [eds], Enterprise and History. Essays in honour of Charles Wilson (Cambridge 1984), p116-134. |

| ↑4 | From the Museum Rotterdam collection in Rotterdam, dated between 1675 and 1700. Apparently market-boats to Norwich and Great Yarmouth left from the quay before this house. |

| ↑5 | The timing of this event is remarkable. Many British shipowners in Rotterdam quickly sold their ships at the start of the war because trade under Dutch or British colours had become too dangerous. P.W. Klein (op.cit. in footnote 3) p131. |

| ↑6 | Norfolk Chronicle, Saturday 20 September 1783, page 4. Via The British Newspaper Archive (£). This painting of a Dutch fair on the beach at Yarmouth by George Vincent (1796–1831) is dated 1821 and is currently in the collection of Elizabethan House Museum in Great Yarmouth. |

| ↑7 | Bengt Ferrner, Resa i Europa 1758-1762 (Uppsala 1956), p129. He wrote this on 2 July 1759, the first day of his stay at Rotterdam. |

| ↑8 | W.J.L. Poelmans, ‘Monté (de)-Lombe’, in: De Nederlandsche Leeuw, jrg. 42 (1924), columns 154-155. See for some info on Robert Partridge sr: P.W. Klein (op.cit. in footnote 3), pp125 and 129. |

| ↑9 | Leydse courant, Ao 1739, No 102 (26 August 1739), front page, “NEDERLANDEN.“. Scroll down to the text under the header Rotterdam. |

| ↑10 | National Archives, E 190; Exchequer: King’s Remembrancer: Port Books; E190/580/3, ‘Yarmouth, Controller Overseas, Xmas 1774 – Xmas 1775’. I’d like to take this opportunity to thank the team of Conversation Technicians at the NA, who have been very helpful and forthcoming in preparing items pertaining to ‘Yarmouth’ before my visits. |

| ↑11 | National Archives, E 190/580/3 (op.cit. in footnote 10). Phinn arrived on 10 April 1775, six days after the ‘date stamp’ on the bill. |

| ↑12 | National Archives, E 190/580/3 (op.cit. in footnote 10). His ship arrived on 17 April 1775. |

| ↑13 | Unfortunately we don’t know how many plants formed a Bunch. Given the similar ‘Value on Oath’ provided for both (£2-5-0 vs £2-7-6), the number of plants may have been the same. But at this point it’s not possible to make an educated guess. |

| ↑14 | From 1776 onwards the records for this customs office became less detailed and only the total numbers of incoming goods per quarter were registered. Ports of origin were reduced to country of origin and the names of ships and captains were not identified anymore. |

| ↑15 | Saunders’s News-Letter of Friday 10 February 1775, p2. Via The British Newspaper Archive (£). There are more examples of these kind of adverts in Saunders’s Newsletter during the decade. |

| ↑16 | The Port Books do not provide enough information to directly connect either transport to the sender or receiver on the bill, Pennystone or De Monté. |

| ↑17 | Essex Record Office; D/DBy A33/6, Audley End estate, Household and Estate Papers 1775. |

| ↑18 | The words ‘Pennystone’, ‘/allden’ and ‘Essex’ can still be read. |

| ↑19 | J.D. Williams, Audley End. The Restoration of 1762 – 1797, Essex Record Office publications, No. 45 (Chelmsford 1966), p46. |