In an earlier post we’ve looked at the place where Humphry Repton lived during his first year at school in the Netherlands (1764-1765), and established that this must have been Woudrichem. Repton himself was not located, but his schoolmaster Egidius Timmerman lived there at the Hoogstraat.1I have called him schoolteacher in my earlier post, but since he owned the school, schoolmaster seems to be a better term. As discussed in the previous post: Timmerman was appointed schoolmaster in the city school, but simultaneously owned and ran his own boarding school, a commercial enterprise. Even today, a side street of the Hoogstraat in Woudrichem is called the Schoolstraat, the name indicating where the only school erected by the city council would have been.

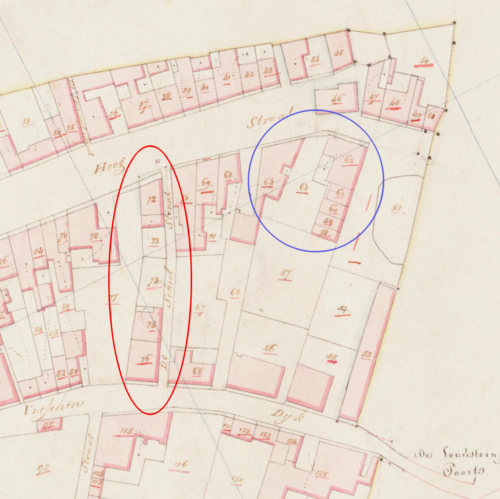

In Timmerman’s time that school was on the western side of the Schoolstraat, behind the ‘Hoofdwacht’ (a police building) on the corner of the Hoogstraat and Schoolstraat, marked nrs. 72 and 73 on this much later map.2In 1805 the school apparently moved elsewhere. Bert van Straten, Woudrichem, een greep uit de historie (Almkerk 1989), p29. The survey map dates from between 1811 and 1832.

In Timmerman’s time that school was on the western side of the Schoolstraat, behind the ‘Hoofdwacht’ (a police building) on the corner of the Hoogstraat and Schoolstraat, marked nrs. 72 and 73 on this much later map.2In 1805 the school apparently moved elsewhere. Bert van Straten, Woudrichem, een greep uit de historie (Almkerk 1989), p29. The survey map dates from between 1811 and 1832.

In 1762 Timmerman bought properties on the Hoogstraat, marked nrs 62 and 63 in the blue circle. This map dates from at least 50 years later, and nr 63 may have still contained a house when Timmerman bought it.3I thank local researcher Ferd C. van Roode for compiling historical data and an overview of owners per house in Woudrichem here (and here for these houses in particular), and Hanna Visser-Kieboom for pointing me to this source.

I think I would disagree with Van Roode’s conclusion that Timmerman’s purchases would represent current street numbers 46 and 48. Given its position relative to the unnamed alley on the opposite side of the street, current nr 46 seems to be nr 64 on the map here, thus neighbouring Timmerman’s properties. But since I didn’t do the ‘legwork’, I’ll be happy to stand corrected. Apparently Timmerman’s own house doubled as his boarding school, which means that Repton must have resided in this property opposite Woudrichem Town Hall (nr 46).4Van Straten, op.cit., p34 suggests Timmerman used his house. It is not important with respect to Repton, but since Timmerman made this purchase 14 years after starting his boarding school, one wonders where that initial boarding school was located. Also in 1762, he had his request granted that the pupils of the ‘Nederduitse’ school could be put up in his own house for the winter. According to Timmerman the school building itself was too cold to be able to hold lessons there. The city counsel approved, on the condition that Timmerman could not use the school building to his own advantage (Van Straten, op.cit., p32.).

I said that the reason why Repton ended up in Woudrichem, may have had something to do with Rotterdam. What follows here are my speculations about the people who may have been involved. (Like me, you of course love speculations. But a word of caution: there is no garden at all in this post.)

Main points

Few things are certain after this exercise, but I do hope some of the ideas presented here can be elaborated on by others. A few preliminary conclusions:

- Humphry Repton’s father may have used his merchant contacts in Norwich to choose Rotterdam as a destination for his son

- He may also have known (of) the Hope family through their ownership of malting houses in Ipswich, Stowmarket and Bury St Edmunds – but that is a long shot

- Humphry Repton may have ended up being schooled in Woudrichem due to the Van der Palm brothers, who were on very relevant positions in Rotterdam and Woudrichem – although their connection with Zachary Hope or father Repton is not clear

- Another likely, but equally unsubstantiated connection may be Hugh Kennedy, minister of the Scottish Church in Rotterdam at the time

Rotterdam, education

We know from his biography that Rotterdam was of importance for this part of Repton’s life, because that is where his father left a sum of money in the care of the merchant Zachary Hope, to pay for his son’s education.5A.B., ‘Biographical notice of the late Humphry Repton, Esq.’, in: J.C. Loudon, The landscape gardening and landscape architecture of the late Humphry Repton (London 1840), p1-22. Link; p7. Given the continuous presence of a large contingent of British merchants in Rotterdam during the 18th century, sending your English speaking child there to learn Dutch seems a logical step.6See P.W. Klein, ”Little London’: British merchants in Rotterdam during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’, in: D.C. Coleman and Peter Mathias [eds.], Enterprise and history; Essays in honour of Charles Wilson (Cambridge 1984), p116-134. The Hope family -of Scottish descent, though present in the Rotterdam area for two generations already- apparently owned a malting house in Bury St Edmunds till at least 1720.7The family also owned malting houses in Ipswich (where they kept two boats for specific transport), Stowmarket, and another place with a short name ending with ‘ton’. See Marten G. Buist, At spes non fracta. Hope & Co. 1770-1815 (The Hague 1974), p4 for a reference. But the mutual will dated 30 March 1720 of Zachary’s parents in which these malting houses were mentioned, was revoked on 31 August 1723 (Stadsarchief Rotterdam [SAR], Oud Notarieel Archief [ONA], inv.nr 2099, fol.492), in favour of an older non-mutual version dated 17 May 1714 (SAR, ONA, inv.nr 1508, fol.352). Apart from the 1720 version, these malting houses never appear in their wills again. This fact may have been instrumental for father Repton to contact one of the last male members of that family still living in Rotterdam.8Most of Zachary Hope’s older brothers had meanwhile moved to Amsterdam where they formed a banking business that would soon become one of the most important financial institutions in that city. During the Seven Year’s war (1756-1763) many British governmental loans to pay for the war efforts, were set up via the Hope family office in Amsterdam (see Buist, op.cit., p11-12; the Netherlands officially remained neutral in this war). Whether father Repton actually knew any member of the Hope family before coming to Rotterdam, is unknown. There were several merchants in Rotterdam at the time with roots in Norwich, though.

Important factors in this part of Repton’s story are the way education was commonly organised in the Netherlands and the role played by church and clergy.9Rotterdam had three churches catering to the English community: the English-Presbytarian church; the English-Episcopical church and the Scottish church. Woudrichem seems to have just the one Dutch Reformed church. Many denominations organized their own education and schools. The following does not apply to the so-called ‘Latin Schools’, where pupils were prepared for further education. Council-led schools, or city schools, were overseen by a combination of the local council, the church council and local ministers.10The supervision of the clergy over schools lasted well into the 19th century, see Van Straten, p29. Lessons were heavily tilted towards religious exercise: pupils learned spelling and reading by studying the scripture and other religious texts; schoolmasters prepared the children weekly for Sunday psalms; and the fact that Timmerman was also expected to act as lead singer in church is by no means an exception.

Important factors in this part of Repton’s story are the way education was commonly organised in the Netherlands and the role played by church and clergy.9Rotterdam had three churches catering to the English community: the English-Presbytarian church; the English-Episcopical church and the Scottish church. Woudrichem seems to have just the one Dutch Reformed church. Many denominations organized their own education and schools. The following does not apply to the so-called ‘Latin Schools’, where pupils were prepared for further education. Council-led schools, or city schools, were overseen by a combination of the local council, the church council and local ministers.10The supervision of the clergy over schools lasted well into the 19th century, see Van Straten, p29. Lessons were heavily tilted towards religious exercise: pupils learned spelling and reading by studying the scripture and other religious texts; schoolmasters prepared the children weekly for Sunday psalms; and the fact that Timmerman was also expected to act as lead singer in church is by no means an exception.

But in his role as a boarding school proprietor, Timmerman was more independent and within limits could develop his own teaching methods. For the country at large, serious educational improvements were presented in 1781.11Herman Jan Krom, Cornelis van der Palm, Dirk Cornelis van Voorst, Gerard Johan Nahuys, Pieter Gilissen, Verhandelingen over de verbeteringe der openbaare, vooral der Nederduitsche schoolen, ter meerdere beschavinge van onze natie (Middelburg 1781). Part of the improvements brought forward here resulted from ‘experiments’ in the city of Rotterdam during the two decades preceding publication, executed by several of the authors.12A.M. van der Giezen, ‘Onderwijs en armenzorg in de achttiende eeuw’, in: Mens & Maatschappij, Vol. 22, Nr. 5 (1947), p278-287. In the 1781 publication the quality of schoolmasters was blasted, stating that these positions were often given to ‘dysfunctional servants’ and people unfit or simply ‘too lazy to do other work’.13Cd. Busken Huet, Litterarische fantasien en kritieken. Deel 24 (1884), p202-203 quotes Van der Palm: ‘Moet men zich niet ten uiterste verwonderen, dat een groot aantal Meesters buiten staat zijn een behoorlijken brief te schrijven? wat zeg ik, te kunnen boekstaven of spellen? Hoe klein is het aantal dergenen die eenige, zelfs maar geringe kennis hunner moederspraak hebben? In steden ziet men veelal schoolmeesters die nergens minder dan tot dien post opgeleid zijn; menschen die, te traag om te werken, dit zittende leven verkozen hebben. Eertijds plag men op de Dorpen meer te zien op eene schoone stem, om eenige toonen langdradig op te dreunen, dan op een verstandig en deugdzaam man. Ik zwijg van zulke oorden daar men aan onbekwame dienstboden, die men anders niet wel wist te plaatsen, het schoolmeesterambt opgedragen heeft.’ There is no information whether any of this applies to Timmerman. But young Humphry Repton certainly was not impressed.14A.B., op.cit., p7-8. Possibly because he had been reading the classics in Norwich, something which Timmerman did not seem to be offering in his boarding school.

The Van der Palm brothers

We’ll probably never know for certain how Repton ended up in Woudrichem. But a relevant link between Rotterdam and Woudrichem during his time there is easily established. Given the above it should not come as a surprise that clergy is involved. My main candidates are two brothers, born in ‘s-Hertogenbosch: Arnoldus and Cornelis van der Palm.

Between 1759 and 1776, Arnoldus van der Palm was ‘predikant’, or minister, in the Dutch reformed church in Woudrichem.15‘Predikant’ can best be translated as ‘minister’ of the Dutch reformed church, which was the dominant religious denomination in the country and in Woudrichem. Arnoldus van der Palm had his first official appearance in Woudrichem on 13 May 1759, as successor of the retiring minister Francois Kuypers.16See this source, fol.4 (login or registering is required since 13 December 2017). Around that same time his younger brother Cornelis set up his own boarding school in Rotterdam, where he had lived and been working as a teacher since 1753/4.17His name is often written starting with the letter ‘K’ too. Nineteenth century biographies of Cornelis van der Palm are abundant, the most complete in terms of personal data can be found here (1888-91).

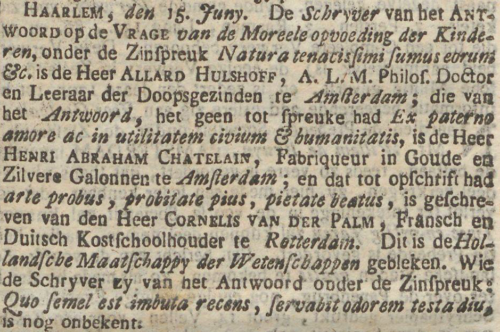

Young Cornelis had been sailing to and from Batavia between 1749 and 1752, after which Arnoldus took him under his wings while preaching in ‘Bommel’.18Modern day Den Bommel, here (I had to look that up). They seem to have remained close ever since. Cornelis van der Palm would become one of the authors of the 1781 publication mentioned above. His efforts to improve educational standards in Rotterdam resulted in the compilation of popular textbooks on speaking Dutch in 1769.19Cornelis van der Palm, Nederduitse Spraakkunst voor de Jeugt; uit verscheidene onzer beste Spraakkunst Schrijvers opgesteld (Rotterdam 1769). Earlier, in June 1765, his entry in a ‘contest’ of the Dutch Society of Sciences (Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen) on the subject of ‘the moral education of children’ received special acclaim.20See the newspaper clipping, source here. A later biography specifies the subject to ‘How can we direct and educate the mind and heart of children, for them to eventually develop into happy and diligent citizens?'21J.G. Frederiks en F. Jos van den Branden, Biographisch woordenboek der Noord- en Zuidnederlandsche letterkunde (Amsterdam 1888-1891), p586-587. Which reminds me of the passage in Repton’s biography where the importance of following one’s passion (to use a modern phrase) is stressed.22A.B., op.cit., p6.

Young Cornelis had been sailing to and from Batavia between 1749 and 1752, after which Arnoldus took him under his wings while preaching in ‘Bommel’.18Modern day Den Bommel, here (I had to look that up). They seem to have remained close ever since. Cornelis van der Palm would become one of the authors of the 1781 publication mentioned above. His efforts to improve educational standards in Rotterdam resulted in the compilation of popular textbooks on speaking Dutch in 1769.19Cornelis van der Palm, Nederduitse Spraakkunst voor de Jeugt; uit verscheidene onzer beste Spraakkunst Schrijvers opgesteld (Rotterdam 1769). Earlier, in June 1765, his entry in a ‘contest’ of the Dutch Society of Sciences (Hollandsche Maatschappij der Wetenschappen) on the subject of ‘the moral education of children’ received special acclaim.20See the newspaper clipping, source here. A later biography specifies the subject to ‘How can we direct and educate the mind and heart of children, for them to eventually develop into happy and diligent citizens?'21J.G. Frederiks en F. Jos van den Branden, Biographisch woordenboek der Noord- en Zuidnederlandsche letterkunde (Amsterdam 1888-1891), p586-587. Which reminds me of the passage in Repton’s biography where the importance of following one’s passion (to use a modern phrase) is stressed.22A.B., op.cit., p6.

Zachary Hope’s son Archibald (born in 1747) may not have been enlisted in Cornelis van der Palm’s boarding school, but regardless it is very improbable that the ‘Fransch en Duitsch kostschoolhouder’ and Hope did not know each other. As a Mennonite, for whom this subject was so important that married couples promised in testaments to provide their children with proper education, Hope would have at least recognized Van der Palm’s drive to improve educational standards.23I use ‘Mennonite’ here as a more familiar term for the Dutch word ‘Doopsgezind’. Buist (op.cit, p4) refers to the majority of the Hope family as ‘Quakers’. Although Zachary’s mother was indeed a Quaker and they are certainly part of the same religious spectrum, I do believe that you can’t lump Quakers and Mennonites together this easy. That may have lead him to ask Cornelis van der Palm for directions where to send Humphry Repton to school.

Timmerman and ministers in Woudrichem and Rotterdam

Arnoldus van der Palm and Egidius Timmerman were certainly acquainted, cooperating in the small city of Woudrichem. In his capacity as lead singer in church, Egidius Timmerman must have dealt with Arnoldus van der Palm at least once a week. After a new Dutch rendering of the Psalms was published, Van der Palm encouraged Timmerman and his pupils to practice more often in order to speed up their grasp of the new texts.24Van Straten, op.cit., p32: “(…) diende Meester Timmerman, op een verzoek van dominee Arnoldus van der Palm, om ‘met het singen wat rasser voort te gaan’ tweemaal per week ‘met sijne discipilen en ieder die lust en genegenheyd heeft’ in de kerk te gaan om deze te instrueren in het ‘singen van de Nieuwe Rijm Psalmen’.”

That Timmerman may have had more than a ‘business’ relationship with the local minister seems to be indicated by an issue that involved Francois Kuypers, Van der Palm’s predecessor, and Kuypers’ son Gerardus.25See for their biography Jan Pieter de Bie, Johannes Lindeboom en G.P. van Itterzon, Biographisch woordenboek van protestantsche godgeleerden in Nederland (‘s-Gravenhage 1943), deel 5, resp. p410-416 and p416-432. Gerardus Kuypers was part of a set of young and rather successful ministers in Nijkerk around the year 1750. Their ‘performances’ on Sunday started to physically affect an increasing part of the congregation, in what he considered a positive way. In reaction to his words, people often started shouting and screaming, and sometimes even had convulsions because of his preaching. After a while, people prone to be affected heavily were placed near the exits of the local church as a precaution. The ‘Nijkerkse Beweging’ was born.26Also referred to as ‘Nijkerkse Beroeringen‘. More (in Dutch) here. For an English reference, see footnote 29.

That Timmerman may have had more than a ‘business’ relationship with the local minister seems to be indicated by an issue that involved Francois Kuypers, Van der Palm’s predecessor, and Kuypers’ son Gerardus.25See for their biography Jan Pieter de Bie, Johannes Lindeboom en G.P. van Itterzon, Biographisch woordenboek van protestantsche godgeleerden in Nederland (‘s-Gravenhage 1943), deel 5, resp. p410-416 and p416-432. Gerardus Kuypers was part of a set of young and rather successful ministers in Nijkerk around the year 1750. Their ‘performances’ on Sunday started to physically affect an increasing part of the congregation, in what he considered a positive way. In reaction to his words, people often started shouting and screaming, and sometimes even had convulsions because of his preaching. After a while, people prone to be affected heavily were placed near the exits of the local church as a precaution. The ‘Nijkerkse Beweging’ was born.26Also referred to as ‘Nijkerkse Beroeringen‘. More (in Dutch) here. For an English reference, see footnote 29.

This lead to two reactions: more people came to church, but the more traditional part of the congregation was not amused. According to them the effects of God’s word should be internalized in silence and dignity, and there was nothing dignified about shouting and having convulsions. In 1750, Gerardus became embroiled in a very public dispute with his former teacher, Leiden theologian Johan van den Honert. This soon took the form of a modern day internet forum or Twitter exchange, partly consisting of deliberate ‘fake news’: very relevant arguments put forward by both sides, were sandwiched between the wildest accusations and rumours. All this ‘information’ and subsequent rebuttals were publicly exchanged via newspapers or heavily advertised -and discussed- pamphlets and publications. Even Francois once publicly defended his son, responding on his behalf to accusations put forward in an anonymus publication.27Francois Kuypers, Godgeleerde oefening over Psalm 24:14, gehouden in de herberg tot Nieuwkerk op de Veluwe, met een omstandig Verhaal over de Uitwerkselen en Gevolgen, die dezelve aldaar gehad heeft, tot vriendelijke en getrouwe Onderrichting van den Schrijver der Aenmerkingen op het Verhaal en de Apologie van Do. Gerardus Kuipers, door Francois Kuypers, predikant te Woudrichem (1749/1750).

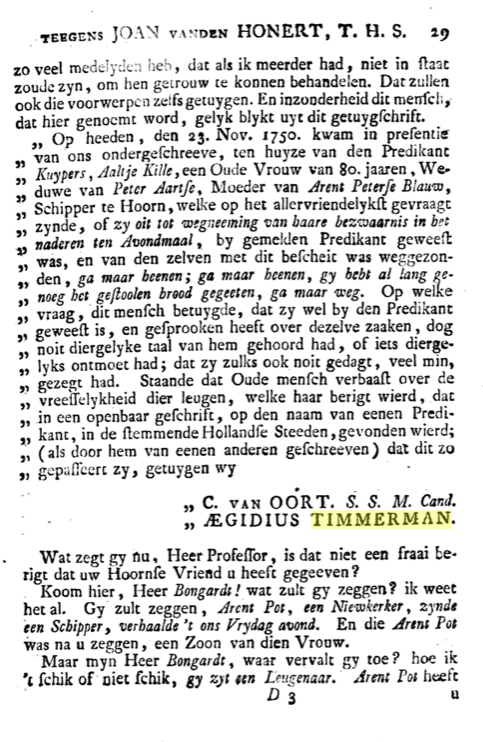

Timmerman had only just entered the scene in Woudrichem at the time, but it seems he was quickly employed by minister Francois Kuypers. In 1751 Gerardus Kuypers published a very long rebuttal of accusations made against him by Van den Honert and others. An Aegidius Timmerman is named twice as a witness to fact-checking conversations Kuypers held with people who -according to his accusers- had said negative things about him.

Timmerman had only just entered the scene in Woudrichem at the time, but it seems he was quickly employed by minister Francois Kuypers. In 1751 Gerardus Kuypers published a very long rebuttal of accusations made against him by Van den Honert and others. An Aegidius Timmerman is named twice as a witness to fact-checking conversations Kuypers held with people who -according to his accusers- had said negative things about him.

Although the connection has -I believe- never before been made, it is difficult not to think of ‘our’ Egidius Timmerman here.

Hugh Kennedy

This is not only relevant because of the connection between the Kuypers family and Timmerman. One of the people supporting Gerardus Kuypers was Hugh Kennedy, minster of the Scottish Church in Rotterdam between 1737 and 1764.28Hugh Kennedy died on 3 November 1764, so he may have seen Repton arrive in Rotterdam. Kennedy published about the broader movement Gerardus Kuypers belonged to in 1752. Written in English and published in London with a British audience in mind, Kennedy emphasized the similarities between developments in Holland and those of the Methodist movement in Britain and the Scottish Revival.29Hugh Kennedy, A short account of the rise and continuing progress of a remarkable work of grace in the United Netherlands (London 1752). A reference in Dutch to his works and writing is found here. Their active involvement in this episode raises the possibility that Hugh Kennedy was another linking pin between Rotterdam and Timmerman at the time Repton was looking for a good school.

And to at least end this post-without-gardens with an estate: Hugh Kennedy was supposedly born in modern Northern Ireland, but was called to Rotterdam in April 1737 from Cavers, ‘in the presbytery of Jedburgh’.30SAR, toegangsnummer 926.01, Archives of the Scots Church Rotterdam (Schotse Kerk), inv.nr 24, Index of documents related to the Ministers of the Scotch Church at Rotterdam, 29 April, 1737. The parish Cavers lies around 10 miles south-west of Jedburgh, a city in the Scottish Borders region. Long a home to the Douglas family, Cavers House is now an empty shell, but there still is an ‘auld kirk’ on its (former?) premises.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | I have called him schoolteacher in my earlier post, but since he owned the school, schoolmaster seems to be a better term. As discussed in the previous post: Timmerman was appointed schoolmaster in the city school, but simultaneously owned and ran his own boarding school, a commercial enterprise. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In 1805 the school apparently moved elsewhere. Bert van Straten, Woudrichem, een greep uit de historie (Almkerk 1989), p29. The survey map dates from between 1811 and 1832. |

| ↑3 | I thank local researcher Ferd C. van Roode for compiling historical data and an overview of owners per house in Woudrichem here (and here for these houses in particular), and Hanna Visser-Kieboom for pointing me to this source. I think I would disagree with Van Roode’s conclusion that Timmerman’s purchases would represent current street numbers 46 and 48. Given its position relative to the unnamed alley on the opposite side of the street, current nr 46 seems to be nr 64 on the map here, thus neighbouring Timmerman’s properties. But since I didn’t do the ‘legwork’, I’ll be happy to stand corrected. |

| ↑4 | Van Straten, op.cit., p34 suggests Timmerman used his house. It is not important with respect to Repton, but since Timmerman made this purchase 14 years after starting his boarding school, one wonders where that initial boarding school was located. Also in 1762, he had his request granted that the pupils of the ‘Nederduitse’ school could be put up in his own house for the winter. According to Timmerman the school building itself was too cold to be able to hold lessons there. The city counsel approved, on the condition that Timmerman could not use the school building to his own advantage (Van Straten, op.cit., p32.). |

| ↑5 | A.B., ‘Biographical notice of the late Humphry Repton, Esq.’, in: J.C. Loudon, The landscape gardening and landscape architecture of the late Humphry Repton (London 1840), p1-22. Link; p7. |

| ↑6 | See P.W. Klein, ”Little London’: British merchants in Rotterdam during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’, in: D.C. Coleman and Peter Mathias [eds.], Enterprise and history; Essays in honour of Charles Wilson (Cambridge 1984), p116-134. |

| ↑7 | The family also owned malting houses in Ipswich (where they kept two boats for specific transport), Stowmarket, and another place with a short name ending with ‘ton’. See Marten G. Buist, At spes non fracta. Hope & Co. 1770-1815 (The Hague 1974), p4 for a reference. But the mutual will dated 30 March 1720 of Zachary’s parents in which these malting houses were mentioned, was revoked on 31 August 1723 (Stadsarchief Rotterdam [SAR], Oud Notarieel Archief [ONA], inv.nr 2099, fol.492), in favour of an older non-mutual version dated 17 May 1714 (SAR, ONA, inv.nr 1508, fol.352). Apart from the 1720 version, these malting houses never appear in their wills again. |

| ↑8 | Most of Zachary Hope’s older brothers had meanwhile moved to Amsterdam where they formed a banking business that would soon become one of the most important financial institutions in that city. During the Seven Year’s war (1756-1763) many British governmental loans to pay for the war efforts, were set up via the Hope family office in Amsterdam (see Buist, op.cit., p11-12; the Netherlands officially remained neutral in this war). |

| ↑9 | Rotterdam had three churches catering to the English community: the English-Presbytarian church; the English-Episcopical church and the Scottish church. Woudrichem seems to have just the one Dutch Reformed church. Many denominations organized their own education and schools. The following does not apply to the so-called ‘Latin Schools’, where pupils were prepared for further education. |

| ↑10 | The supervision of the clergy over schools lasted well into the 19th century, see Van Straten, p29. |

| ↑11 | Herman Jan Krom, Cornelis van der Palm, Dirk Cornelis van Voorst, Gerard Johan Nahuys, Pieter Gilissen, Verhandelingen over de verbeteringe der openbaare, vooral der Nederduitsche schoolen, ter meerdere beschavinge van onze natie (Middelburg 1781). |

| ↑12 | A.M. van der Giezen, ‘Onderwijs en armenzorg in de achttiende eeuw’, in: Mens & Maatschappij, Vol. 22, Nr. 5 (1947), p278-287. |

| ↑13 | Cd. Busken Huet, Litterarische fantasien en kritieken. Deel 24 (1884), p202-203 quotes Van der Palm: ‘Moet men zich niet ten uiterste verwonderen, dat een groot aantal Meesters buiten staat zijn een behoorlijken brief te schrijven? wat zeg ik, te kunnen boekstaven of spellen? Hoe klein is het aantal dergenen die eenige, zelfs maar geringe kennis hunner moederspraak hebben? In steden ziet men veelal schoolmeesters die nergens minder dan tot dien post opgeleid zijn; menschen die, te traag om te werken, dit zittende leven verkozen hebben. Eertijds plag men op de Dorpen meer te zien op eene schoone stem, om eenige toonen langdradig op te dreunen, dan op een verstandig en deugdzaam man. Ik zwijg van zulke oorden daar men aan onbekwame dienstboden, die men anders niet wel wist te plaatsen, het schoolmeesterambt opgedragen heeft.’ |

| ↑14 | A.B., op.cit., p7-8. Possibly because he had been reading the classics in Norwich, something which Timmerman did not seem to be offering in his boarding school. |

| ↑15 | ‘Predikant’ can best be translated as ‘minister’ of the Dutch reformed church, which was the dominant religious denomination in the country and in Woudrichem. |

| ↑16 | See this source, fol.4 (login or registering is required since 13 December 2017). |

| ↑17 | His name is often written starting with the letter ‘K’ too. Nineteenth century biographies of Cornelis van der Palm are abundant, the most complete in terms of personal data can be found here (1888-91). |

| ↑18 | Modern day Den Bommel, here (I had to look that up). |

| ↑19 | Cornelis van der Palm, Nederduitse Spraakkunst voor de Jeugt; uit verscheidene onzer beste Spraakkunst Schrijvers opgesteld (Rotterdam 1769). |

| ↑20 | See the newspaper clipping, source here. |

| ↑21 | J.G. Frederiks en F. Jos van den Branden, Biographisch woordenboek der Noord- en Zuidnederlandsche letterkunde (Amsterdam 1888-1891), p586-587. |

| ↑22 | A.B., op.cit., p6. |

| ↑23 | I use ‘Mennonite’ here as a more familiar term for the Dutch word ‘Doopsgezind’. Buist (op.cit, p4) refers to the majority of the Hope family as ‘Quakers’. Although Zachary’s mother was indeed a Quaker and they are certainly part of the same religious spectrum, I do believe that you can’t lump Quakers and Mennonites together this easy. |

| ↑24 | Van Straten, op.cit., p32: “(…) diende Meester Timmerman, op een verzoek van dominee Arnoldus van der Palm, om ‘met het singen wat rasser voort te gaan’ tweemaal per week ‘met sijne discipilen en ieder die lust en genegenheyd heeft’ in de kerk te gaan om deze te instrueren in het ‘singen van de Nieuwe Rijm Psalmen’.” |

| ↑25 | See for their biography Jan Pieter de Bie, Johannes Lindeboom en G.P. van Itterzon, Biographisch woordenboek van protestantsche godgeleerden in Nederland (‘s-Gravenhage 1943), deel 5, resp. p410-416 and p416-432. |

| ↑26 | Also referred to as ‘Nijkerkse Beroeringen‘. More (in Dutch) here. For an English reference, see footnote 29. |

| ↑27 | Francois Kuypers, Godgeleerde oefening over Psalm 24:14, gehouden in de herberg tot Nieuwkerk op de Veluwe, met een omstandig Verhaal over de Uitwerkselen en Gevolgen, die dezelve aldaar gehad heeft, tot vriendelijke en getrouwe Onderrichting van den Schrijver der Aenmerkingen op het Verhaal en de Apologie van Do. Gerardus Kuipers, door Francois Kuypers, predikant te Woudrichem (1749/1750). |

| ↑28 | Hugh Kennedy died on 3 November 1764, so he may have seen Repton arrive in Rotterdam. |

| ↑29 | Hugh Kennedy, A short account of the rise and continuing progress of a remarkable work of grace in the United Netherlands (London 1752). A reference in Dutch to his works and writing is found here. |

| ↑30 | SAR, toegangsnummer 926.01, Archives of the Scots Church Rotterdam (Schotse Kerk), inv.nr 24, Index of documents related to the Ministers of the Scotch Church at Rotterdam, 29 April, 1737. |

Ooo, a community of British merchants in Rotterdam. That’s especially useful to me. Thank you :-)

Great! Good to hear my writing sometimes actually helps others do their research :-)

I hope this usefulness eventually translates into something we can all read some day.