Two stories about trees floating in upright position appeared in the media this month: one related to something that has long been a traditional feature of park landscaping, the other as part of a climate change awareness project. They made me think of an earlier example.

The traditional story comes from Georgia (see this BBC coverage), where a new park is laid out by former prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili. To give his park more ‘body’, mature trees are imported from elsewhere -nothing new in landscape architecture. One of these trees, a Tulip tree of around 100 years old, was uprooted in the west of the country. Its transport by boat over the waters of the Black Sea provided images such as this:

A 100 year-old Tulip tree is transported over the waters of the Black Sea.

Closer to home, Rotterdam saw the eh… ceremonial launch of a Bobbing Forest in the former harbour basin Rijnhaven. This project by Rotterdam art production collective Mothership is inspired by and a cooperation with Columbian artist Jorge Bakker. It takes a somewhat light-hearted approach to problems associated with climate change: the predicted rise of sea levels and its possible consequences for low lying land -like Rotterdam and much of the Netherlands. Even in today’s storm, the trees seem to cope well with the conditions.

The Bobbing Forest in the Rijnhaven. (photos: HvdE).

Pliny the Elder

Both stories made me think of what Pliny the Elder wrote about this part of the world.1Gaius Plinius Secundus, Naturalis Historia, XVI.2.1. Quoted in: Geert Mak, Ooggetuigen van de Nederlandse geschiedenis in meer dan honderd reportages (Amsterdam 2005), p36-37. According to some sources Pliny was in the area of modern Leiden in AD 47, from where a canal between the rivers Rhine and Maas was made by Roman troops. At the height of their expansion into Northwestern Europe, the Romans managed to occupy the southern half of what is now the Netherlands. The larger rivers running towards the North Sea formed a natural boundary along which the border (the ‘limes‘) was formed. The river Rhine was also an important trade route. Peoples living to the north were hostile to the Roman occupation, and they often successfully defended their territory against Roman attacks -in which Pliny himself was involved.2Pliny -whether inspired by frustration or disbelief about their resistance to the superior life style of the Romans- described these people as living in swamps, constantly under threat from flooding, being pushed back to (scarce, and often self-built) higher ground for most of the year. To warm themselves they burned dried ‘mud’ (peat), which, according to Pliny, was dried more by the strong winds than by the warmth of the sun.

Pliny was writing about the Chauci, living between the Weser and the Elbe rivers in modern Germany. But the Chauci traveled westward during Pliny’s lifetime, and were environmentically and culturally strongly related to the Frisii, who lived in the northern part of the Netherlands. To defend themselves against attacks from the north, the Romans created army camps along the border, and they had ships patrolling the rivers.

Pliny notes that at several occasions, Roman sailors thought they were being attacked by enormous enemy ships. In reality, their rigging was wrecked by mature trees, standing on islands floating down the river.3As he wrote: Many is the time that these trees have struck our fleets with alarm, when the waves have driven them, almost purposely it would seem, against their prows as they stood at anchor in the night; and the men, destitute of all remedy and resource, have had to engage in a naval combat with a forest of trees!

Boggy soil, cut loose by high and/or fast floating waters created the islands, only held together by the roots of the trees growing upon them. It must have been a majestic sight to see these trees float towards and onto the sea, comparable with the Tulip tree transport on the Black Sea.

Like the Roman attempts to occupy new territory, the Georgian ‘tree grab’ leads to protests from the locals, who may not be satisfied with the promised replanting of trees for compensation. Collecting mature trees from elsewhere for the benefit of a few individuals is not as acceptable as it seems to have been during the 19th and early 20th centuries, when this was fairly common practice among estate owners and landscape architects. That ‘climate’ seems to have also changed.

2000 years

The Rotterdam project is planned to run between five and ten years, but I think that period should be expanded, provided the elm trees can reach some form of maturity in this environment. We could create a modern version of these ancient floating forested islands by cutting loose bobbing forest in a few decades from now. For example in 2047, exactly two millennia after Pliny supposedly roamed these parts and must have heard his soldiers tell those stories.

I like to think this would both commemorate an important period of our history, and be a strong reminder that climate change played a significant role in the decline and fall of the Roman empire.4Provided we still need this reminder by that time. The Frisii were also forced to leave most of their territory in the fourth century AD, because of flooding caused by… rising sea levels.

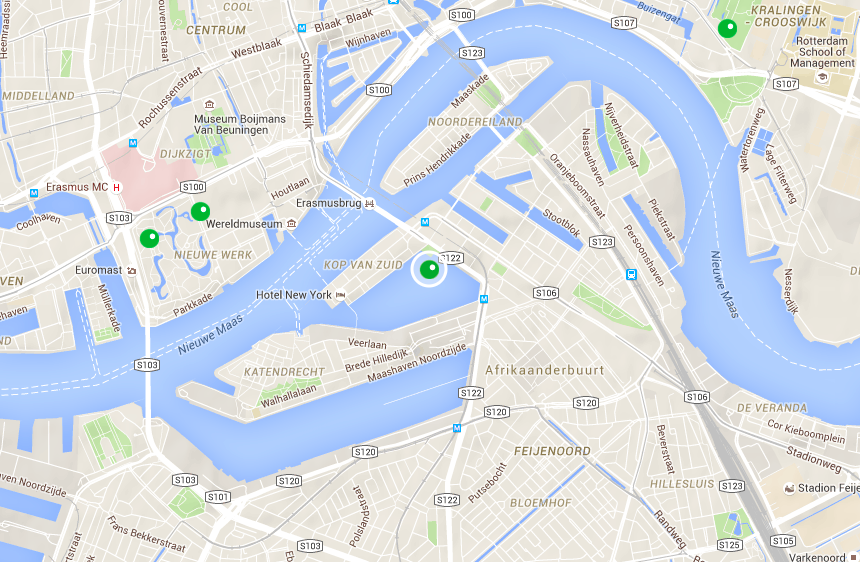

Location of the Bobbing Forest project in the Rijnhaven in Rotterdam.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Gaius Plinius Secundus, Naturalis Historia, XVI.2.1. Quoted in: Geert Mak, Ooggetuigen van de Nederlandse geschiedenis in meer dan honderd reportages (Amsterdam 2005), p36-37. According to some sources Pliny was in the area of modern Leiden in AD 47, from where a canal between the rivers Rhine and Maas was made by Roman troops. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Pliny -whether inspired by frustration or disbelief about their resistance to the superior life style of the Romans- described these people as living in swamps, constantly under threat from flooding, being pushed back to (scarce, and often self-built) higher ground for most of the year. To warm themselves they burned dried ‘mud’ (peat), which, according to Pliny, was dried more by the strong winds than by the warmth of the sun. Pliny was writing about the Chauci, living between the Weser and the Elbe rivers in modern Germany. But the Chauci traveled westward during Pliny’s lifetime, and were environmentically and culturally strongly related to the Frisii, who lived in the northern part of the Netherlands. |

| ↑3 | As he wrote: Many is the time that these trees have struck our fleets with alarm, when the waves have driven them, almost purposely it would seem, against their prows as they stood at anchor in the night; and the men, destitute of all remedy and resource, have had to engage in a naval combat with a forest of trees! Boggy soil, cut loose by high and/or fast floating waters created the islands, only held together by the roots of the trees growing upon them. |

| ↑4 | Provided we still need this reminder by that time. The Frisii were also forced to leave most of their territory in the fourth century AD, because of flooding caused by… rising sea levels. |