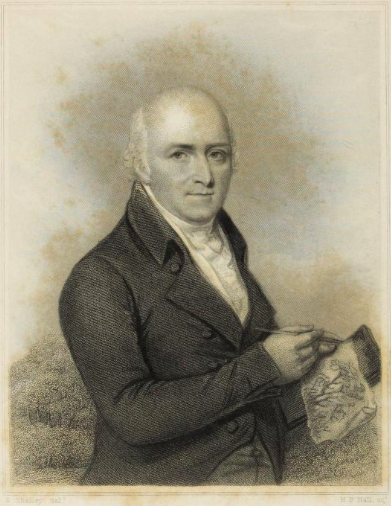

English landscape architect Humphry Repton (1752-1818) will be celebrated in the UK next year, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of his death. Not many people are aware that Repton spent some time in the Netherlands as a youngster, between ages 12 and almost 16. Part of this period he described as quality time, part of it would have made him feel miserable, were he not such a good sport.

English landscape architect Humphry Repton (1752-1818) will be celebrated in the UK next year, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of his death. Not many people are aware that Repton spent some time in the Netherlands as a youngster, between ages 12 and almost 16. Part of this period he described as quality time, part of it would have made him feel miserable, were he not such a good sport.

We learn all this from his biography, published in 1840 and based on his own memoirs, which Repton apparently wrote for his children.

Given the upcoming celebrations, I was curious to see if more information about his tenure here could be found. Unfortunately Repton’s original memoirs covering the first years of his life are currently unavailable, so we have to rely on the at times very detailed information his biography provides, and go from there. Since a boy in his teens usually doesn’t show up in official records unless something bad happens, information is scarce. However, parts of what I did find differ from the information in Repton’s biography.

This post concerns the less pleasant part of his life in the Netherlands: his first twelve months at school. The pronunciation of some words in Dutch plays an important role.

What we think we know

Let’s start with the biography’s version of events. Repton was born in Bury St Edmunds (Suffolk) in 1752 and moved to Norwich (Norfolk) with his family as a child. In the summer of 1764 Repton’s father decided that his son needed to go to the Netherlands. The goal was for him to learn Dutch and to acquire business acumen. According to biographer ‘A.B.’, his father and sister accompanied young Humphry to the continent, where he ended up at a school in Workum. His teacher there was – here the biographer seems to be quoting Repton – ‘Mynheer Algidius Zimmerman’.

Unfortunately part of this information is wrong. His teacher was called Algidius nor Zimmerman, and neither he nor Repton was in Workum. To be fair on Repton and his biographer: the mistakes made are all understandable.

Place

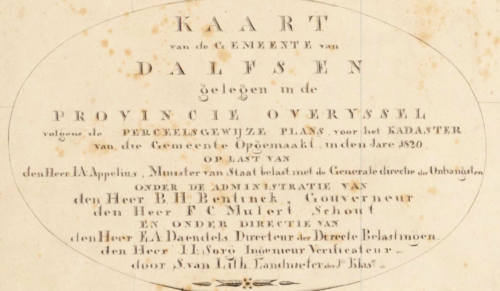

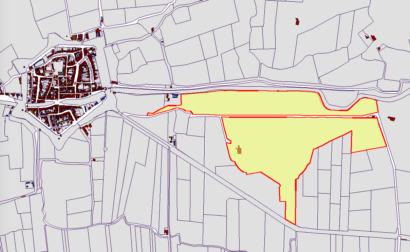

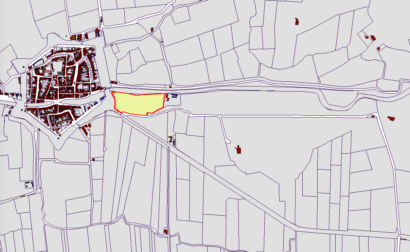

The only Workum one will ever find on a map of the Netherlands, is the city of that name in the province of Friesland, in the north of the country (click on the map to enlarge).

The city had two ‘normal’ schools and a ‘Latin’ school, where upper class children prepared for further studies. Repton could have been schooled here, but Workum is an improbable place to send an English boy to. Apart from very personal connections between the Repton family and someone in Workum, no convincing argument comes to mind.

The city had two ‘normal’ schools and a ‘Latin’ school, where upper class children prepared for further studies. Repton could have been schooled here, but Workum is an improbable place to send an English boy to. Apart from very personal connections between the Repton family and someone in Workum, no convincing argument comes to mind.

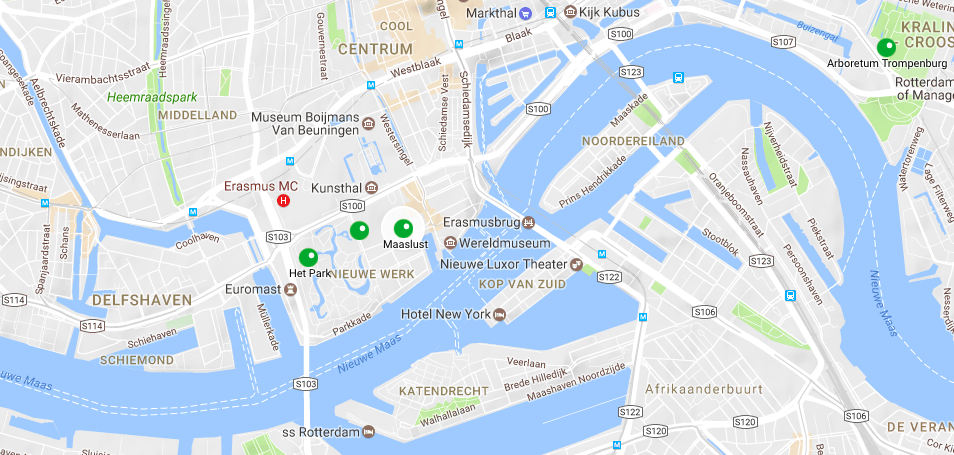

What made it particularly improbable, is that at the time it would have been possible to travel directly by boat from Norwich to Workum. But Repton boarded in Harwich and came ashore in Hellevoetsluis, almost at the other side of the country. From there the journey north would have taken an additional two days.

I could not establish personal connections between the Repton family and someone in Workum. And the fact that no schoolteacher with a name even remotely resembling Algidius Zimmerman could be found anywhere near Workum, lead to the conclusion that neither of them was actually there. Which meant I had to look further.

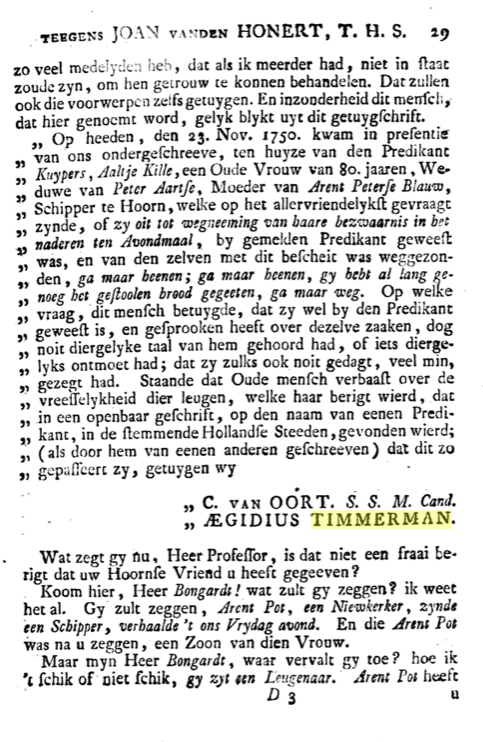

Find the teacher, and we know where Repton was. But Algidius Zimmerman doesn’t seem to exist at all. The more likely alternative name Aegidius didn’t immediately yield results that fit our purpose; and the alternative surname Timmerman is Dutch for ‘carpenter’, thus yielding a million results in genealogical and archival databases. Looking for alternative personal names would obviously not get me anywhere soon.

What to do?

Every next step was going to be a fishing expedition. My idea was that the biographer may have misread or misinterpreted Repton’s writing of the town’s name. And all along there was at least one viable alternative. Much farther south than Workum and not too far east from Hellevoetsluis, is a city that officially goes by the name of Gorinchem, but in normal parlance this is pronounced – and sometimes even written – as Gorkum.

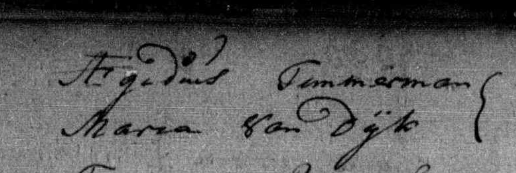

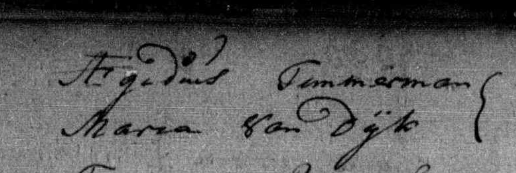

That line of inquiry quickly turned out to be a bust, but the same construction applies to the name of a few other cities and villages in that area. One of these places is just on the other side of the river from Gorinchem, called Woudrichem. Locals pronounce this as Woerkum or even Worcum (the ‘c’ in Worcum is pronounced as the letter ‘k’). Figuring that if this man was a schoolteacher, he should also be a member of the Reformed Church, I started going through the so-called lidmaten register of June 1763.

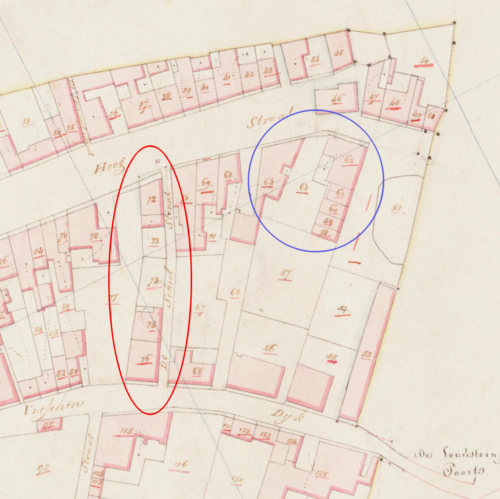

And there I found a man with the at least very similar name Ægidius Timmerman, married to a Maria van Dijk and living on the Hoogstraat in Woudrichem. When it turned out this man had been the only schoolteacher in Woudrichem for over 40 years, I was pretty certain. Not only did I find Repton’s teacher, suddenly there was an abundance of sources mentioning him (none of them naming Repton): from an 1873 article specifically about his boarding school, to a mention in the Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal.

And there I found a man with the at least very similar name Ægidius Timmerman, married to a Maria van Dijk and living on the Hoogstraat in Woudrichem. When it turned out this man had been the only schoolteacher in Woudrichem for over 40 years, I was pretty certain. Not only did I find Repton’s teacher, suddenly there was an abundance of sources mentioning him (none of them naming Repton): from an 1873 article specifically about his boarding school, to a mention in the Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal.

In official documents and on maps, Woudrichem is always referred to under its full name. Repton probably used one of the dialect versions of the cities’ name in his memoirs, leading his biographer (who only had the official names at his disposal) to the wrong city.

Egidius Timmerman and his school(s)

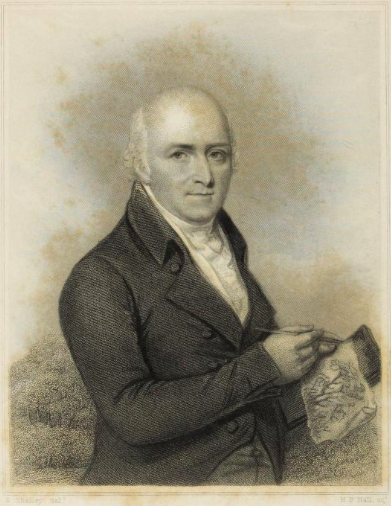

By the time Repton came to Woudrichem, Timmerman had been teacher there for more than fifteen years. Born in Haastrecht in 1723 and with a previous teaching experience in Acquoy under his belt, Timmerman was officially installed as schoolteacher in Woudrichem in 1748. He was assigned to lead the Nederduitse school, which meant his pupils were provided the most basic types of education (spelling, reading Dutch), with a strong emphasis on the scripture and psalms. His other assignment was to be voorzanger (lead singer) in church every Sunday.

By the time Repton came to Woudrichem, Timmerman had been teacher there for more than fifteen years. Born in Haastrecht in 1723 and with a previous teaching experience in Acquoy under his belt, Timmerman was officially installed as schoolteacher in Woudrichem in 1748. He was assigned to lead the Nederduitse school, which meant his pupils were provided the most basic types of education (spelling, reading Dutch), with a strong emphasis on the scripture and psalms. His other assignment was to be voorzanger (lead singer) in church every Sunday.

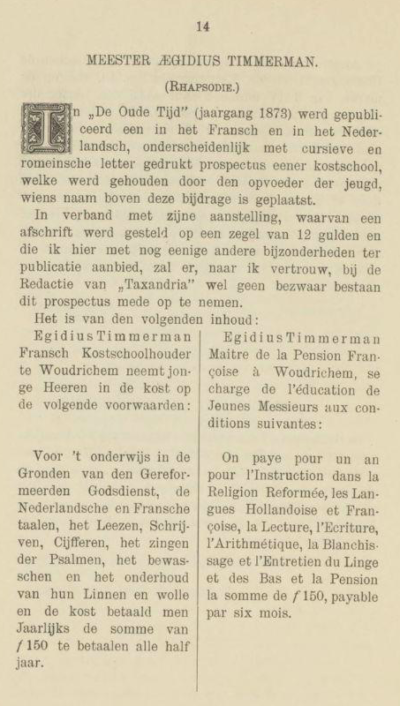

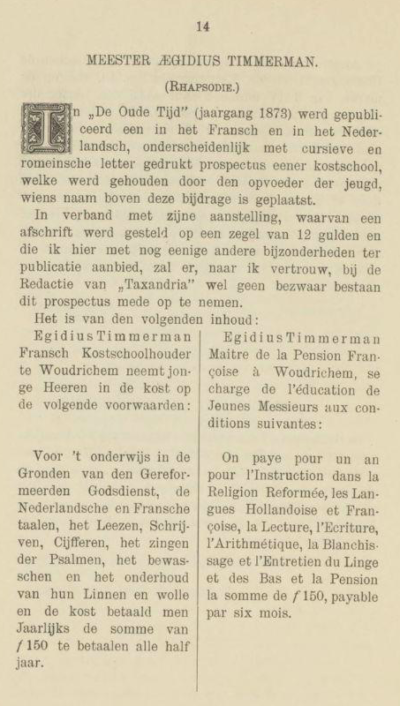

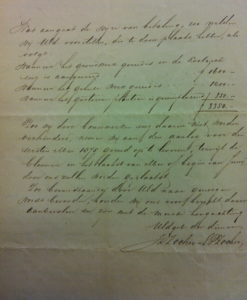

But Humphry Repton probably did not attend this Nederduitse school. Timmerman had started his own ‘French’ boarding school, using the cities’ insistence that only he was allowed to educate people in Woudrichem to his advantage. Timmerman published a prospectus in Dutch and French to advertise his project (republished in both languages here). Apart from prospective pupils having to bring their own napkins, silver cutlery, tin plates and drinking mug, the requirement for semi-annual payments stands out. These neatly align with the ‘half-yearly payments’, mentioned in Repton’s biography. In addition to religious teachings, the Dutch and French languages and arithmetics, Timmerman also provided lessons in bookkeeping. This brings to mind Repton’s remark that “A Dutch merchant’s accounts and his garden were kept with the same degree of accuracy and attention.”

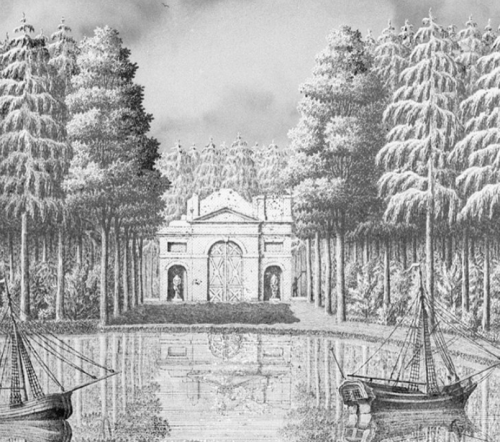

Unknown artist, Garden of Martinus van Barnevelt in Gorinchem, 1760-1770. Collection Gorcums Museum.

Name

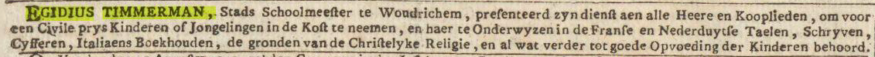

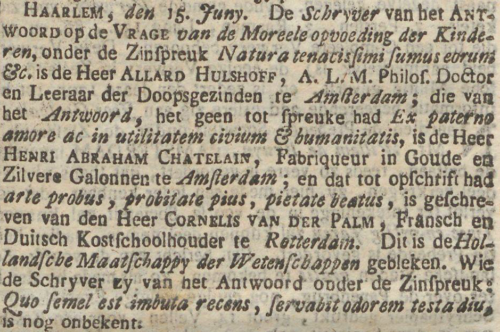

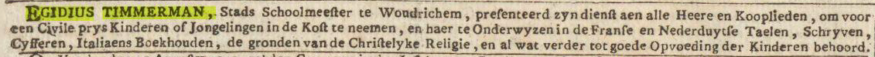

The prospectus also shows that Repton’s teacher referred to himself as Egidius Timmerman. He did the same when he advertised his school in a newspaper in 1749:

This version of his name is corroborated by the entry of his baptism in the Haastrecht church records on 22 March 1723. But during his life (and after, as the article by Kingmans shows), other people often referred to him as Ægidius or Aegidius. Here, again, particular characteristics of the Dutch language are at play. In Dutch all versions sound the same, the ultimate spelling depends on the clerk of the day. Given the fact that in English the ‘E’ and ‘Ae’ at the beginning of a word are often pronounced differently, Repton may have been taught the Aegidius spelling to at least come to the correct pronunciation. Which in turn may have caught his biographer off-guard: a hand-written Aegidius can easily be read as Algidius; the same applies to Timmerman-Zimmerman.

Woudrichem it is!?

Humphry Repton must have spent his first twelve months in the Netherlands in the fortified city of Woudrichem, where (salmon) fishing and agriculture were the main source of income for the 600-700 inhabitants. But apart from its location in the country relative to where Repton landed, Woudrichem seems to be an even more unlikely place than Workum to send an English boy to for educational purposes. There were only two official schools, both lead by Egidius Timmerman. As of yet, I have seen no mention of Repton in local records, and school records do not seem to have survived.

But I believe there is enough additional information to support the idea that Repton lived in Woudrichem, although the evidence remains circumstantial. The linking pins are people living in and connected to the city of Rotterdam.

An upcoming post will look at that in more detail.

Afgelopen week vond de presentatie plaats van alweer het derde boek van Tuinhistorisch Genootschap Cascade. Thema van deze bundel artikelen was ‘verdwenen tuinen’. Daar zijn er nogal wat van in Nederland (en daarbuiten).

Afgelopen week vond de presentatie plaats van alweer het derde boek van Tuinhistorisch Genootschap Cascade. Thema van deze bundel artikelen was ‘verdwenen tuinen’. Daar zijn er nogal wat van in Nederland (en daarbuiten).

I

I

English landscape architect Humphry Repton (1752-1818) will be celebrated in the UK next year, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of his death. Not many people are aware that Repton spent some time in the Netherlands as a youngster, between ages 12 and almost 16. Part of this period he described as quality time, part of it would have made him feel miserable, were he not such a good sport.

English landscape architect Humphry Repton (1752-1818) will be celebrated in the UK next year, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of his death. Not many people are aware that Repton spent some time in the Netherlands as a youngster, between ages 12 and almost 16. Part of this period he described as quality time, part of it would have made him feel miserable, were he not such a good sport.

De enige reden dat L.P. Zocher níet verantwoordelijk zou zijn voor de aanleg van deze tuin, kan het plotselinge overlijden zijn geweest van diens oudste dochter Johanna Jacoba Zocher, op 30 maart 1875.

De enige reden dat L.P. Zocher níet verantwoordelijk zou zijn voor de aanleg van deze tuin, kan het plotselinge overlijden zijn geweest van diens oudste dochter Johanna Jacoba Zocher, op 30 maart 1875.