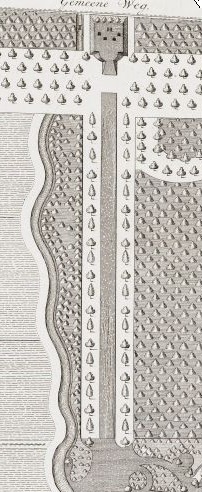

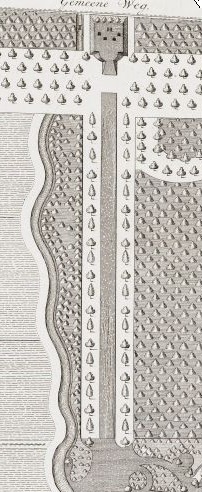

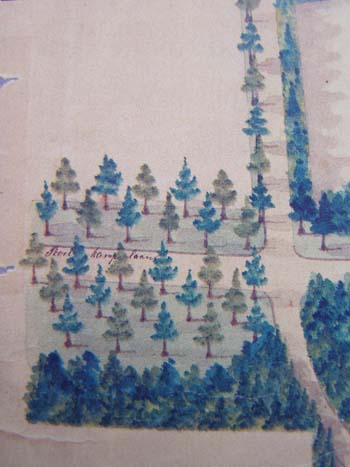

Interesting information has come to my attention in the last few months, and of course it has some bearing on the garden of Beeckestijn: avenues lined with two types of trees. On the Beeckestijn map (1772) we see such an avenue in the continuation of the central axis at the end of the garden, right in front of the colonnade.

Avenues are among the most formal and architectural features in any garden, and although their use may vary (lead the eye to a focal point, connect and pull together different parts of the garden, act as a screen or divider between garden parts), it is almost always characterised by the uniform appearance of similar trees placed in a linear pattern. This uniformity can become dull, and while dullness is not something any garden owner or architect strives for, many variations to the theme have been tried. Thus we find gardens in which the avenues are lined by a combination of different sorts of deciduous trees, like oak and lime. Around 1800 the Champs Elysées in Paris was lined with old chestnut trees, which, according to a visitor, formed a beautiful backdrop for the locust trees (Acacia) also planted there.

What we see less often is an avenue lined with a variety of deciduous and coniferous or evergreen trees. This practise probably began just before the rise of the landscape style on the European continent. The attraction of such a combination is obvious: the avenue always retains some of its green and its capacity to form a screen. The general difference in growth form between the two types of trees is also attractive.

At Beeckestijn this may have been the case: the alternate depiction of ‘normal’ and pyramidal trees at least suggests this mix. We do not know what types of trees were planted here.

There are only a few other examples known in The Netherlands. I mention them here, because I hope to gather more information on this type of planting in avenues. Two of these examples date from the second half of the eighteenth century and the other was designed and planted during the 1890’s.

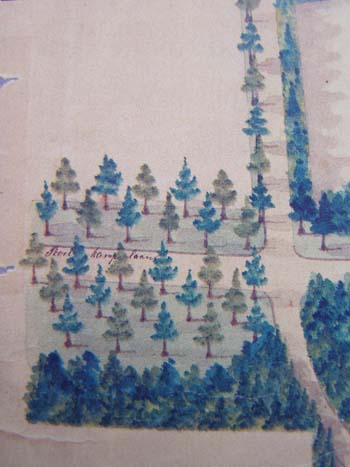

Starting with the latter, the Boombergpark in Hilversum, there was a special purpose to the alternate planting of beech and larch. According to the authors of a recent book on the park, the larches were used as sun blocks, to protect the sensitive bark of the freshly planted beech trees. This view is supported by the fact that the larches were cut out 25 years later because they had “lost their purpose”.  In his design for the Boombergpark in Hilversum, landscape architect Dirk Wattez used this kind of planting for two avenues. One was a single lined, slightly winding avenue on the western side of the park where different kinds of trees are planted alternately along the side of the paths. The other -straight- avenue was on the eastern side of the park, with two rows of trees on one side and three on the other (see right hand image). Where there are three rows of trees, they are planted in a quincunx formation, with again alternating sorts along the roadside. Wattez used a smart pattern here, because his plantation was set up in such a way, that from whichever way one looked, there were never three trees of the same species planted in one line. So although the larches may only have had a practical use in the end, Wattez made sure they made an aesthetic impression while they lasted.

In his design for the Boombergpark in Hilversum, landscape architect Dirk Wattez used this kind of planting for two avenues. One was a single lined, slightly winding avenue on the western side of the park where different kinds of trees are planted alternately along the side of the paths. The other -straight- avenue was on the eastern side of the park, with two rows of trees on one side and three on the other (see right hand image). Where there are three rows of trees, they are planted in a quincunx formation, with again alternating sorts along the roadside. Wattez used a smart pattern here, because his plantation was set up in such a way, that from whichever way one looked, there were never three trees of the same species planted in one line. So although the larches may only have had a practical use in the end, Wattez made sure they made an aesthetic impression while they lasted.

The two 18th century examples are Beeckestijn and Twickel. The original planting of both avenues is long gone, leaving us with no information about the species planted there. Two contemporary German examples, of which we do know which species were used, show some possibilities.

The first is not far from The Netherlands, in fact just over the border with Germany in the garden of Kleef (Kleve). In 1781 an avenue of beech and fir was mentioned by Pieter van Winter. Van Winter admired the contrast between the colours and texture of both sorts (bright green and soft for the beech; paler green and needle-like for the fir tree). He also says the trees had grown considerably since he saw them earlier, which indicates the trees must have been planted somewhere in the 1760’s or 1770’s.

The second German example is near Aschaffenburg: Schönbusch. Like Beeckestijn, this garden was a mix of baroque elements and landscape garden design, although the execution of the landscape garden at Schönbusch was much bolder than the Dutch garden. For a more formal part of the garden, head gardener Müller was told by the Prince-Elector (Kurfüst) to transform a chestnut avenue into a mixed avenue. He was ordered to plant large larches between the chestnuts: “(…) [zwischen] 2 Kastanien-Baümen jedesmalen ein wohlgewachsener Lerchenbaum hineingepflanzet werden solle (…)“. The reaction of the Prince-elector’s advisor Sickingen is telling: he thinks this is not a good idea, because in his view planting larches between chestnuts in a straight avenue alongside water is of and old fashioned artificiality that was not suitable for a modern garden like Schönbusch.

Going back to Beeckestijn, current belief is that this mixed avenue was planted between 1755 and 1760. This fits in with what both German examples show: planting mixed avenues was en vogue in the third quarter of the 18th century. It appears to have been swept away by the landscape style coming in from England during that same period. Some of the early landscape gardens kept these mixed avenues intact, possibly because they were still deemed to be modern enough to last for a while.

During the reconstruction ten years ago, in a long and difficult discussion about what to plant here, a compromise was reached: a combination of lime and thuja was planted in this avenue. I was present at that discussion and I believe it is safe to say that none of the participants was happy with this choice. But politically it was the only combination possible at the time.

During the reconstruction ten years ago, in a long and difficult discussion about what to plant here, a compromise was reached: a combination of lime and thuja was planted in this avenue. I was present at that discussion and I believe it is safe to say that none of the participants was happy with this choice. But politically it was the only combination possible at the time.

Back then, the information cited above was not available to the restoration team. Now Beeckestijn is on the threshold of a new start, and the thuja’s are suffering and lagging behind the lime trees (or just plain dead), it is not too late to use this information and do the right thing: dig out the thuja’s and plant firs or larches instead.

Please. It can be done in the next months.

It grew in the garden of Beeckestijn, which is not far from the coast -and thus already in a milder climate because the relatively higher temperature of the sea water dampens the effects of winter in this part of the country. In the article the plant was called a “Pyrus Japonica” and it is possible that here the Pyrus japonica (Thunb) is meant; we now know this plant as Chaenomeles japonica, a prickly plant bearing fruit that ripens very late in the year.

It grew in the garden of Beeckestijn, which is not far from the coast -and thus already in a milder climate because the relatively higher temperature of the sea water dampens the effects of winter in this part of the country. In the article the plant was called a “Pyrus Japonica” and it is possible that here the Pyrus japonica (Thunb) is meant; we now know this plant as Chaenomeles japonica, a prickly plant bearing fruit that ripens very late in the year.

In his design for the Boombergpark in Hilversum, landscape architect Dirk Wattez used this kind of planting for two avenues. One was a single lined, slightly winding avenue on the western side of the park where different kinds of trees are planted alternately along the side of the paths. The other -straight- avenue was on the eastern side of the park, with two rows of trees on one side and three on the other (see right hand image). Where there are three rows of trees, they are planted in a quincunx formation, with again alternating sorts along the roadside. Wattez used a smart pattern here, because his plantation was set up in such a way, that from whichever way one looked, there were never three trees of the same species planted in one line. So although the larches may only have had a practical use in the end, Wattez made sure they made an aesthetic impression while they lasted.

In his design for the Boombergpark in Hilversum, landscape architect Dirk Wattez used this kind of planting for two avenues. One was a single lined, slightly winding avenue on the western side of the park where different kinds of trees are planted alternately along the side of the paths. The other -straight- avenue was on the eastern side of the park, with two rows of trees on one side and three on the other (see right hand image). Where there are three rows of trees, they are planted in a quincunx formation, with again alternating sorts along the roadside. Wattez used a smart pattern here, because his plantation was set up in such a way, that from whichever way one looked, there were never three trees of the same species planted in one line. So although the larches may only have had a practical use in the end, Wattez made sure they made an aesthetic impression while they lasted. During the reconstruction ten years ago, in a long and difficult discussion about what to plant here, a compromise was reached: a combination of lime and thuja was planted in this avenue. I was present at that discussion and I believe it is safe to say that none of the participants was happy with this choice. But

During the reconstruction ten years ago, in a long and difficult discussion about what to plant here, a compromise was reached: a combination of lime and thuja was planted in this avenue. I was present at that discussion and I believe it is safe to say that none of the participants was happy with this choice. But  Be that as it may, the more interesting question is whether all lions share the same provenance. This is suggested by their similar appearance.

Be that as it may, the more interesting question is whether all lions share the same provenance. This is suggested by their similar appearance. If we were to play a match on Beeckestijn by modern standards, we would be forced to play on a field just next to the garden proper, now in use as a meadow for horses (see my poor rendering of that situation on the left).

If we were to play a match on Beeckestijn by modern standards, we would be forced to play on a field just next to the garden proper, now in use as a meadow for horses (see my poor rendering of that situation on the left).