Today a month ago the 2013 Painshill Conference, titled ‘Gardens of Association: the Roles and Meanings of Garden Buildings in Eighteenth Century Landscapes’, kicked off for a remarkable two days of lectures and discussion. I do not intend (or pretend) to write a review of this great and interesting conference, but there are some points I’d like to highlight.

The conference itself began with a broad look at types of garden buildings, went on to gradually focus on more specific types, uses and the (possible but often contested) meanings and iconographies of these structures. The harking back to Anglo-Saxon legacy by both Whigs and Tories; the neo gothic and its different connotations for Catholics and reformed garden owners/garden visitors; and the changing iconography of Stowe after the British victory in the Seven Years war -they all made an appearance. Towards the end of the conference the focus went more and more towards one of the main features at Painshill itself, the recently restored crystal grotto:

Painshill, the restored crystal grotto. Photo: Painshill Park Trust, 2013.

The following are just a few personal observations during these two days.

Mount Edgcumbe garden building vs. the Bidloo garden in Moscow.

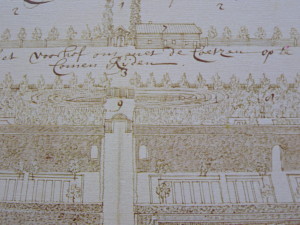

Richard Hewlings showed a picture of an 18th century drawing of a garden building at Mount Edgcumbe (near Plymouth). I don’t have it here, but the most important feature of that picture for me was not the building, but the planting of evergreens surrounding it. That immediately brought to mind the drawing on the left, by and of the garden of the Dutch physician Nicolaas Bidloo, near Moscow (see this previous post).

Richard Hewlings showed a picture of an 18th century drawing of a garden building at Mount Edgcumbe (near Plymouth). I don’t have it here, but the most important feature of that picture for me was not the building, but the planting of evergreens surrounding it. That immediately brought to mind the drawing on the left, by and of the garden of the Dutch physician Nicolaas Bidloo, near Moscow (see this previous post).

I think the author of the Mount Edgcumbe drawing was called Prudeau Edmund Prideaux (1693-1745), drawing this around 1727 -according to my notes. I hope this drawing is published somewhere, but I didn’t get that impression at the time. So you’ll just have to take my word for it, but if we do away with the fence in the Bidloo drawing and replace the gardener with the Mount Edgcumbe garden building, the resemblances are remarkable. Bidloo‘s drawing dates from the same period (late 1720s), but was never published till the 1970s. Could he have known the Mount Edgcumbe drawing? Or could the circular area -with or without building- surrounded by a thick planting of evergreens have been the norm at the time?

Stourhead vs Rievaulx Terrace .

Oliver Cox was invited to talk about his view on the attempts to explain Stourhead‘s iconography over the last decades. Like he did earlier in his article in the GHS journal, Cox ‘condemned’ (nicely) academic disregard for contemporary garden visitors’ descriptions. 1Oliver Cox, ‘A mistaken iconography? Eighteenth-century visitor accounts of Stourhead’, in Garden History 40:1 (2012), p.98-116. These visitors never gave any indication of being aware of even the existence of an iconographic program in the garden of Stourhead, let alone that they made attempts to explain it.

Michael Symes, in another context, used the term ‘iconographic phallacy’ to describe how an intended iconography, deliberatly used by the garden owner and/or garden designer, could sometimes not land with the garden’s visitors and therefore remain largely unnoticed. It doesn’t mean the iconography wasn’t there, it just wasn’t picked up.

But that is of course the usual slippery slope iconographical explanations -without solid backing from contemporary sources- have always had to deal with, a situation that will always have to be taken into account. In that sense Cox’s sceptic approach can only be applauded.

But one argument Cox uses to underline his point strikes me as odd. He mentions that in c1818 a guide to the garden of Stourhead was published, in which the entrance was on a totally different place than where modern ‘academics’ thought it had been. The routing of the garden was different, therefore the garden buildings were not approached in the careful order suggested by the advocates of different iconographical explanations -who relied on this particular routing. 2Oliver Cox, op.cit., p.104.

Cox combines this with the lack of iconographic references in visitors’ accounts, to question modern ‘academia’ in their attempts to impose an iconography on Stourhead gardens.

My objection would be that this c1818 guide was published over half a century after most garden buildings at Stourhead had been built, or at least conceived. It is not impossible that two generations later, the garden was conceived in a different light and that certain changes in taste were followed by adaptations in the layout. I don’t see how this entrance being on another location then could say anything worthwhile about the situation 50 to 60 years earlier, without evidence supporting the fact that the entrance had been on that location all along. As that evidence is not supplied, I can’t help but conclude that Cox is replacing one ‘slippery slope’ by another.

Speaking of slopes: it is here where Rievaulx Terrace comes into play, as far as I am concerned. Just half an hour earlier, dr Patrick Eyres was speaking at the conference. He mentioned, that where the approach to Rievaulx Terrace in the 1770s focussed on the views at the low lying ruined abby from the terrace, that situation seems to have changed by 1820. Then, at least one account heralds the view at Rievaulx from the valley the abbey was built in. Turner’s 1836 watercolor also uses that lower view point. Could this same movement have happened at Stourhead? And thus caused the entrance to be relocated to a position more suitable to the early 19th century taste?

This doesn’t necessarily mean that the overall approach to British gardens -and the elements in them- changed to such an extend between 1760 and 1820, that in some cases (quite literally) the approach or entrance itself needed to be changed. There are practical reasons to think of in the case of Rievaulx Terrace: maybe the views from above were overgrown and not discernable anymore. But this is a subject that is worthwhile investigating.

Tea house activities

I’d like to end this on a much lighter note. As we’re on ‘slippery slopes’ anyway, I’ll descend a little bit further to embrace another garden building ‘association’. While summarizing one of the lectures, conference chairman Tim Richardson said in a by-line: “There’s not much else one can do in an open structure like a Chinese tea house, than, well… have tea.” From a Western viewpoint, he is probably right. But I’d recommend a visit to the British Museum’s current Shunga exposition exhibition, to see how these buildings could also be used -in their original context, both in Japan and China (and maybe provided one’s teahouse has a second floor).

See the video for a ‘curators introduction’ to this exhibition, the caption image is a tea house scene already.