You may ask yourself: “What does a picture of the moon have to do with historical gardens?”. My answer: more than you presumably think (and the fact that it is a great picture is in itself reason enough to show it here). 1Source: mattie_shoes photostream on flickr For example: for centuries gardeners have loosely scheduled large portions of their work -pruning, sowing, harvesting- on the moon’s cycle. 2Gardener’s calendars at least until the end of the 18th century have an abundancy of references like this: “sow after the third new moon of the year” -although the religious calendar was very important as well, but in reformed Holland the saints -for obvious reasons- were not as important as elsewhere.

You may ask yourself: “What does a picture of the moon have to do with historical gardens?”. My answer: more than you presumably think (and the fact that it is a great picture is in itself reason enough to show it here). 1Source: mattie_shoes photostream on flickr For example: for centuries gardeners have loosely scheduled large portions of their work -pruning, sowing, harvesting- on the moon’s cycle. 2Gardener’s calendars at least until the end of the 18th century have an abundancy of references like this: “sow after the third new moon of the year” -although the religious calendar was very important as well, but in reformed Holland the saints -for obvious reasons- were not as important as elsewhere.

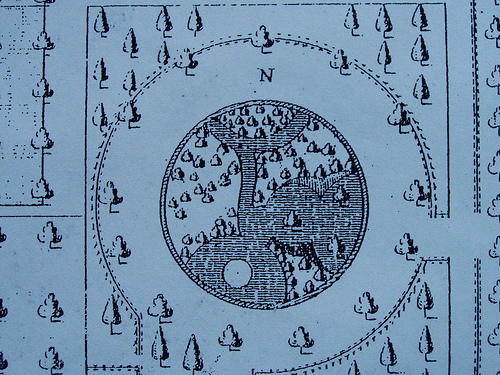

Another way in which gardens and the moon can interact, is the way it is done at Beeckestijn. There, on the 1772 map of the estate, part of the menagerie is a circle with a plan that can best be described as a stylised map of the moon: the bright spot in the lower part of the circle is on the same location as the large crater on the moon’s surface, known as Tycho crater.  The other forms and shapes -in essence: the lights and darks- may not resemble the moon for a bit, but that is less important. I’ll try to explain why I think that is the case -and why I believe this part of the garden symbolises the moon.

The other forms and shapes -in essence: the lights and darks- may not resemble the moon for a bit, but that is less important. I’ll try to explain why I think that is the case -and why I believe this part of the garden symbolises the moon.

Quality of the available source material is one of the issues to address. The large crater can be spotted with the naked eye (even from the largely urbanised place where I live, with nothing but ‘light pollution’ around), whereas the other parts of the surface can be difficult to discern without the right gear and instruments. To us, the actual surface of the moon is known and available in an instant, through top of the range telescopes, photography and internet. For people in the 1760’s, when this garden was laid out in the form known to us through the 1772 estate map, that wasn’t the case. Ofcourse people knew what the moon looked like, they may have looked at it better than most of us ever have. But we know what the moon ‘exactly’ looks like just because we have good representations of the moon’s surface at hand, enabling us to better understand the surface than we would ever be able to by seeing for ourselves. What they saw, is exactly the same as what we see. But their representations of the moon have left more room for interpretation than ours.

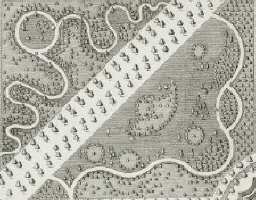

The picture on the right is such a contemporary representation of the moon’s surface. It was published in what in those days must have been the benchmark of knowledge: l’Encyclopedie by Diderot. This image is taken from the Astronomie-section in the VIIth part of that immense work, which was published in 1767-68. 3The image is rotated, not just to put it in the same direction as the other images used here, but because we actually see the moon like this at our longitude. The Beeckestijn version must have been created in the same period: the style of the design is very much in line with what we know about the early landscape style, adopted in The Netherlands around 1755, but slowly finding its way into Dutch society during the 1760’s and 1770’s. It shows the same view of the moon we have today. The engraving is a fairly exact representation of the moon’s actual surface, but there are slight differences, caused mainly by the coarseness of the engraving. Apparently this image was deemed a good enough representation of the moon; we could all go out at night and see for ourselves to check. But it is also a highly schematic representation of the moon, which allows room for interpretation and different views.

Thinking along those lines there is another issue: we must ask ourselves how important it may have been for the designers and owners of Beeckestijn to recreate an exact image of the moon’s surface. The fact that it sort-of resembled the moon might have been sufficient, just like the fact that Beeckestijn’s triumphal arch was probably painted on a piece of wood and would only have looked real from a distance. There are many, many more examples of these practices in The Netherlands throughout the ages, I mentioned a contemporary one earlier, from an English student in Leyden, traveling between Delft and Leyden in 1765:

‘The passage there is very pleasant, the gardens of the Merchants running the whole way down the river; by what I can see of the Dutch gardens they are infinitely inferior to ours, & seem to be greatly behind us in Taste, their only ecxellence is their neatness which is extraordinary – their decoration is odd, they fill their gardens with paintings, & if they want to lengthen a walk, they paint a gravel one on a piece of board, to deceive the Eyes & I saw more than one painted Aviry (sic)’. 4 He means to say: Aviary. James Harris to his father, September 16, 1765. Source: Hamphire Record Office (Winchester, England), Malmesbury family archive, inventory 9M73, inv.nr 262/5

Besides that it still is a garden and no matter what message someone wants to convey with the design of parts of the garden, it still needs to be practical. In this case this means that where copying the exact surface of the moon would have left the owner with an unpleasant walk, the surface is stylised and adapted in such a way as to primarily work as a garden feature, and secondly convey an inaccurate, yet convincing image of the moon.

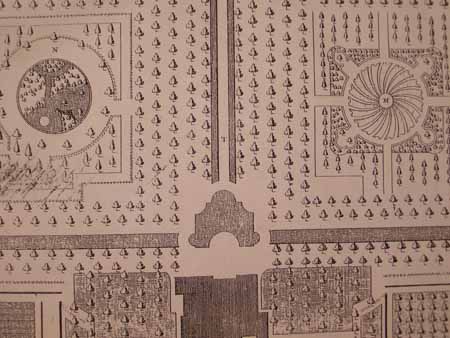

The interpretation of this garden feature is in my view obvious when we notice a similar styling on the opposite side of the central axis at Beeckestijn, where the flower garden forms a mirror-feature of the menagerie, both near to, and at the same distance from, the main house. 5The main house is the dark blob below in the centre.  Here we see a circular form, consisting of bend curved flower beds spiralling outward from an open centre. These spiralling flower beds can be viewed seen as the rays of the sun, and the whole flower garden as a representation of the sun. Both features have been identified as the moon and sun before. 6Joke van der Aar & Siebe Rolle, Een beeld van een buitenplaats: de tuinen van Beeckestijn, Museum Beeckestijn, Velsen-Zuid, 2000, p44-45. There is one problem with this identification: it can only be presented in a convincing way, when we take both features into account. It is difficult to prove these identifications when we focus at each individual feature.

Here we see a circular form, consisting of bend curved flower beds spiralling outward from an open centre. These spiralling flower beds can be viewed seen as the rays of the sun, and the whole flower garden as a representation of the sun. Both features have been identified as the moon and sun before. 6Joke van der Aar & Siebe Rolle, Een beeld van een buitenplaats: de tuinen van Beeckestijn, Museum Beeckestijn, Velsen-Zuid, 2000, p44-45. There is one problem with this identification: it can only be presented in a convincing way, when we take both features into account. It is difficult to prove these identifications when we focus at each individual feature. We cannot be sure whether these designs actually stand for the sun and moon, but it seems likely.

We cannot be sure whether these designs actually stand for the sun and moon, but it seems likely.

To return to the central topic with a question: why would someone be keen to have the moon visualised in the menagerie of his garden? There are many posible answers possible to that question, and it is very tempting to put one of these forward as a definitive one. But the truth is we don’t know at all. It is quite possible both garden feautures represented the ‘male’ (sun, flowergarden) and the ‘female’ (moon, menagerie), as we see happening in more gardens in The Netherlands: like an echo of the prince and princesse’s gardens at Paleis Het Loo in the 17th century. Antoher possibility is one that has been linked with the 1772 map earlier by Heimerick Tromp, where various garden features are said to contain symbols that point towards the Freemason movement. 7Cascade 15 [2006], nr. 2, p. 6-13. In Freemasonry, the sun and the moon are important elements. In this case he also identifies the moon on the 1772 map, but in a different section of the garden.  The then owner of Beeckestijn, Jacob Boreel Jansz., is not listed as a freemason, but two of his grandsons (one also called Jacob, the other Willem François) became one later on. A tantalising hint towards Mrs. Boreel also being interested in the Freemasons comes from a letter sent to her husband Jacob by a friend, Cornelis Backer. At the time, Jacob Boreel was in London, sent out as an envoy on behalf of the Dutch government. It was his responsibility to maintain the right for Dutch ships to transport goods during the Seven Year’s War (in which The Netherlands were neutral, but the English accused the Dutch of transporting goods on behalf of the French, with whom England was at war -ofcourse we never did such a thing :0). 8Holland wanted to hold on to a free-trade treaty both countries agreed upon in 1674. England felt the treaty was outdated and -mainly- did not serve their needs anymore, as England was on the rise and Holland had become an ecomically less important state. Cornelis Backer wrote on the 11th of June 1759:

The then owner of Beeckestijn, Jacob Boreel Jansz., is not listed as a freemason, but two of his grandsons (one also called Jacob, the other Willem François) became one later on. A tantalising hint towards Mrs. Boreel also being interested in the Freemasons comes from a letter sent to her husband Jacob by a friend, Cornelis Backer. At the time, Jacob Boreel was in London, sent out as an envoy on behalf of the Dutch government. It was his responsibility to maintain the right for Dutch ships to transport goods during the Seven Year’s War (in which The Netherlands were neutral, but the English accused the Dutch of transporting goods on behalf of the French, with whom England was at war -ofcourse we never did such a thing :0). 8Holland wanted to hold on to a free-trade treaty both countries agreed upon in 1674. England felt the treaty was outdated and -mainly- did not serve their needs anymore, as England was on the rise and Holland had become an ecomically less important state. Cornelis Backer wrote on the 11th of June 1759:

“Hede morgen had ik de Eer te ontfangen die van UHEdGest. der 8 jongstleden; ik heb daar op de papieren van UHEdGestr. rakende de free masson van Mevrouw Boreel; onder mijne recepisse ontfangen en zal daar op alvorens te berichten (…) met den Heer R.P. in den Haag spreeken.” 9A selfmade translation, using some shortcuts: “This morning I received your [letter] dated June 8. I have also received your papers with regard to the Freemasons of Mrs. Boreel”. He goes on saying that he will discuss the matter with one of the highest politicians (the mentioned “R.P.”, which are not his initials, but those of his function: Raadspensionaris. I have yet to find an English equivalent for that. His name was Pieter Steyn, though.) in Holland, and he’ll reply on the subject later on. Source: Nationaal Archief, Boreel family archive, inventory 1.10.10, inv.nr 132.Cornelis Backer was the owner of Sandenhoeff, a small estate in Overveen.

Sadly, we don’t have the original letter and papers Boreel sent, and a reply on the subject is also missing (or: not found yet). It is strange that it was Mrs. Boreel who is mentioned in relation to this, because as far as I know, the Freemasons remained a strictly male brotherhood until the end of the 19th century.

In conclusion (for now): I believe the layout of the menagerie at Beeckestijn is meant to represent the full moon. It is not a direct copy of the moon’s surface, mainly because that probably was not important but it would also not be usefull as a garden feature people should be able to walk through. The date of the design must lie between 1760 and 1772, but it is possble the design leans heavily on the engraving in the Encyclopedie, pushing the date forward to between 1768 and 1772. The reason why Jacob Boreel chose to depict the moon in his menagerie is unknown, even when we take into account that it mirrors a representation of the sun on the other side of the central axis.

Comments and suggestions are very welcome.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Source: mattie_shoes photostream on flickr |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gardener’s calendars at least until the end of the 18th century have an abundancy of references like this: “sow after the third new moon of the year” -although the religious calendar was very important as well, but in reformed Holland the saints -for obvious reasons- were not as important as elsewhere. |

| ↑3 | The image is rotated, not just to put it in the same direction as the other images used here, but because we actually see the moon like this at our longitude. The Beeckestijn version must have been created in the same period: the style of the design is very much in line with what we know about the early landscape style, adopted in The Netherlands around 1755, but slowly finding its way into Dutch society during the 1760’s and 1770’s. |

| ↑4 | He means to say: Aviary. James Harris to his father, September 16, 1765. Source: Hamphire Record Office (Winchester, England), Malmesbury family archive, inventory 9M73, inv.nr 262/5 |

| ↑5 | The main house is the dark blob below in the centre. |

| ↑6 | Joke van der Aar & Siebe Rolle, Een beeld van een buitenplaats: de tuinen van Beeckestijn, Museum Beeckestijn, Velsen-Zuid, 2000, p44-45. There is one problem with this identification: it can only be presented in a convincing way, when we take both features into account. It is difficult to prove these identifications when we focus at each individual feature. |

| ↑7 | Cascade 15 [2006], nr. 2, p. 6-13. In Freemasonry, the sun and the moon are important elements. |

| ↑8 | Holland wanted to hold on to a free-trade treaty both countries agreed upon in 1674. England felt the treaty was outdated and -mainly- did not serve their needs anymore, as England was on the rise and Holland had become an ecomically less important state. |

| ↑9 | A selfmade translation, using some shortcuts: “This morning I received your [letter] dated June 8. I have also received your papers with regard to the Freemasons of Mrs. Boreel”. He goes on saying that he will discuss the matter with one of the highest politicians (the mentioned “R.P.”, which are not his initials, but those of his function: Raadspensionaris. I have yet to find an English equivalent for that. His name was Pieter Steyn, though.) in Holland, and he’ll reply on the subject later on. Source: Nationaal Archief, Boreel family archive, inventory 1.10.10, inv.nr 132.Cornelis Backer was the owner of Sandenhoeff, a small estate in Overveen. |