Previously on this blog:

1. I discovered a striking similarity between lion statues placed at De Paauw (ca. 1855, Wassenaar, The Netherlands) and at Drottningholm (ca. 1865, Stockholm, Sweden).

2. Before I came round to explaining how these estates, and therefore the statues, were related through the Dutch Royal family at the time, I found more similar lion statues in the garden of Powerscourt (1850-1867, Wiclow, Ireland), whose owner does not seem to have had any relationship at all with that Royal family.

3. A description of that garden gave us the source for all of these lion statues: the Egyptian statues situated at the bottom of the stairs to the Palatine mountain in Rome.

So we have three instances where similar lion statues appear in gardens across Northern Europe, in a very limited period: between 1850 and 1867. And their inspiration, which is much older, originated far more south and travelled across the Mediterranean from Egypt to Rome.

So we have three instances where similar lion statues appear in gardens across Northern Europe, in a very limited period: between 1850 and 1867. And their inspiration, which is much older, originated far more south and travelled across the Mediterranean from Egypt to Rome.

This all suggests a sculptor’s studio produced copies of the original in small numbers, during a short period in the third quarter of the 19th century.

And then photo’s of Scott fountain at Belle Isle Park started to appear in the photo group on Flickr. This fountain was started in 1919, finished in 1925 and created by architect Cass Gilbert and sculptor Herbert Adams. Around the base four lions play a role in the elaborate waterworks of the fountain.

And then photo’s of Scott fountain at Belle Isle Park started to appear in the photo group on Flickr. This fountain was started in 1919, finished in 1925 and created by architect Cass Gilbert and sculptor Herbert Adams. Around the base four lions play a role in the elaborate waterworks of the fountain.

The similarities with the 19th century statues are obvious. Compared to the ones at De Paauw (above) the Detroit statues (right) show the details in more relief, but the lions in Wassenaar seem to have the smoothest finish of them all. Seen from the side the Belle Isle Park lions look very much like the originals in Rome (see the HGimages link below this post for more photos).

But the gap between the occurance of these statues is over half a century.

Why Herbert Adams (1858-1945) used these lions, and where he got his inspiration from, is material for further research. He went to Europe in the 1880s, where he worked for French sculptor Antonin Mercié, who consequently created two statues in the US in 1890 and 1891.

Adams’ work consists mainly of busts and statues of people, he may even have only sculpted the Scott-statue situated near the fountain. In that case Cass Gilbert (1859-1934) could have chosen to install exactly these four lion statues on the fountain.

Amidst all the uncertainties, it is clear that the Palatine lions remained an inspiration for sculptors far into the 20th century, even outside Europe. Whether they were mass produced as copies since the 1850s, or whether they kept inspiring individual artists over and over again, remains to be seen.

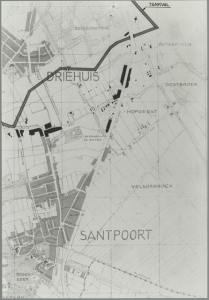

I don’t know when the current situation was created, but it obviously misses the elegance of the original layout. The idea of blocking the view at the wall was clearly better than the current situation. The retaining wall is similar to electricity units or other utility buildings in gardens: they are necessary, but one doesn’t want to see them. Plants are used to cover things up. In Dutch a term for that kind of planting is ‘schaamgroen’, a degrading term which practically reflects the reason of its existence and also the poor quality of the way these areas are generally fitted into larger historical layouts. But the tiny postcards above show that it doesn’t have to be that way.

I don’t know when the current situation was created, but it obviously misses the elegance of the original layout. The idea of blocking the view at the wall was clearly better than the current situation. The retaining wall is similar to electricity units or other utility buildings in gardens: they are necessary, but one doesn’t want to see them. Plants are used to cover things up. In Dutch a term for that kind of planting is ‘schaamgroen’, a degrading term which practically reflects the reason of its existence and also the poor quality of the way these areas are generally fitted into larger historical layouts. But the tiny postcards above show that it doesn’t have to be that way.