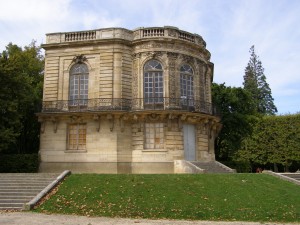

Last september I spotted a little gem in the public park of Sceaux, just south of Paris: the Pavillon de Hanovre. It stands there as the natural focal point of a patte d’oie. The avenues leading from (or to) the building are all neatly pruned to reproduce the 18th century environment this pavilion needs. In short: it stands there like it is built for the spot. And in certain ways it is, more about that later.

Last september I spotted a little gem in the public park of Sceaux, just south of Paris: the Pavillon de Hanovre. It stands there as the natural focal point of a patte d’oie. The avenues leading from (or to) the building are all neatly pruned to reproduce the 18th century environment this pavilion needs. In short: it stands there like it is built for the spot. And in certain ways it is, more about that later.

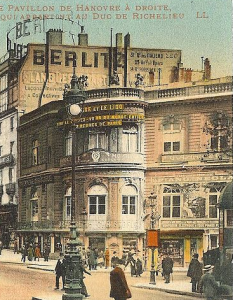

I was surprised to find out that this pavilion was placed here only 80 years ago (in 1932), after it had been removed from a bustling Paris boulevard (as can be seen on this postcard) to make room for the Palais Berlitz.

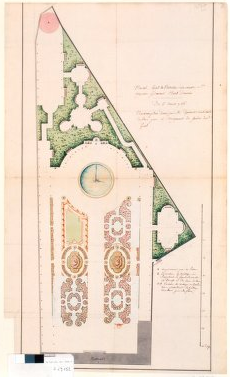

There, on the corner of the Boulevard des Italiens and the rue Louis-le-Grand, the pavilion was originally designed in 1756 at the end of the garden of Hôtel d’Antin (indicated by the red circle), the Paris dwelling of Maréchal de Richelieu. It was built between 1758 and 1760. The pavilion’s name probably refers to Richelieu’s occupation of Hanover in late 1757, but as this initially successful campaign ended in his sudden resignation in a storm of accusations (corruption being only one of them) early in 1758, that seems a bit odd. The designs made in august 1756 originated at a happier time: just after the more successful endeavour on Minorca, which took place between April and June 1756.

There, on the corner of the Boulevard des Italiens and the rue Louis-le-Grand, the pavilion was originally designed in 1756 at the end of the garden of Hôtel d’Antin (indicated by the red circle), the Paris dwelling of Maréchal de Richelieu. It was built between 1758 and 1760. The pavilion’s name probably refers to Richelieu’s occupation of Hanover in late 1757, but as this initially successful campaign ended in his sudden resignation in a storm of accusations (corruption being only one of them) early in 1758, that seems a bit odd. The designs made in august 1756 originated at a happier time: just after the more successful endeavour on Minorca, which took place between April and June 1756.

Rebuilt, or built anew?

Situating this pavilion at Sceaux formed part of the restoration of is its gardens between 1928 and 1932. All online sources I have seen go on to say that the pavilion was ‘rebuilt’ here, but we’ll see that that is not entirely the case. Admittedly, it took me a while to spot the differences, but they are noticeably abundant.

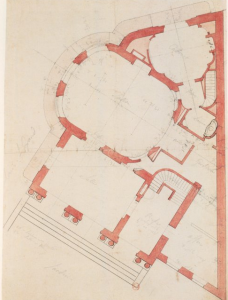

First of all, the current building misses one complete storey: either the complete second floor was lost in transport, or they decided to do without the first floor. Slightly less conspicuous is the fact that in its original state -and very much in line with architectural fashion in 1756- the Pavillon de Hanovre was an asymmetrical building, as opposed to its current perfect symmetry. The images below illustrate those points.

Ground plan and original location.

Architect Chevotet produced several designs for the pavilion (they can be found here along with some 18th century views and early photographs), but this ground plan seems to be the closest match to the actual building. 1When Chevotet made his designs he also worked on the gardens at Beloeil in Belgium.  We see the asymmetry in both images. I hope the photo I made conveys the pavilion’s current symmetry. What should at least be clear is that the left side of the pavilion retained its original form, with the angle in its façade. New is that the right side mirrors the left façade. All sides do now face one of three avenues leading up to (or from) the building: the patte d’oie. 2This patte d’oie itself seems to be a new invention as well: it does not show up on 17th designs or maps of the park.

We see the asymmetry in both images. I hope the photo I made conveys the pavilion’s current symmetry. What should at least be clear is that the left side of the pavilion retained its original form, with the angle in its façade. New is that the right side mirrors the left façade. All sides do now face one of three avenues leading up to (or from) the building: the patte d’oie. 2This patte d’oie itself seems to be a new invention as well: it does not show up on 17th designs or maps of the park.

The pavilion was planned and built here in 1932 by the architect responsible for the restoration of Sceaux’s park, Léon Azéma. He also restored the Grandes Cascades elsewhere in the park, using mascerons made by Auguste Rodin. So Azéma was not afraid to combine old and new. Together with architects Louis Plousey and Urbain Cassan he relocated the Pavillon de Hanovre to the most logical spot it could have in this park. But they also made sure their signature was all over the building.

The adaptations may have been forced upon them: building material could have been in such a bad state after disassembly, that they could only create a smaller version. But to me it seems they made some deliberate choices: a two-storey building would have been too big in this part of the park; and the symmetry may be seen as an hommage to the style of the great architect of Sceaux’s original garden, whose design features were still quite visible in the by then somewhat dilapidated park: André le Notre. 3Le Notre designed the park after 1670, for Jean-Baptiste Colbert. The dilapidated state of the park is visible in photos made by Eugene Atget between March and June 1925. Many of them can be seen here.

When we look at Pavillon de Hanovre in the park of Sceaux, we see a 20th century rendition of an 18th century garden pavilion. The original 18th century building materials are shaped and bent in a way that makes it fit neatly into a restored, predominantly 17th century French garden. The architects did not just rebuild the disassembled pavilion: they created their own.

The new, symmetrical Pavillon de Hanovre in its (relatively) new setting. Use the ‘HGmap’ link under this post to zoom in on the park.

[Edited for spelling]

Footnotes

| ↑1 | When Chevotet made his designs he also worked on the gardens at Beloeil in Belgium. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This patte d’oie itself seems to be a new invention as well: it does not show up on 17th designs or maps of the park. |

| ↑3 | Le Notre designed the park after 1670, for Jean-Baptiste Colbert. The dilapidated state of the park is visible in photos made by Eugene Atget between March and June 1925. Many of them can be seen here. |

There is a painting of the pavillion de Hanovre by Francois Debret (1777-1850) that looks like it was painted in Napoleon’s time, on page 75 of Views of Paris by Eric Hazan (Bibliotheque nationale de France,2013). The building in the painting looks very much like the rebuilt one in Parc de Sceaux minus a charming cupola/penthouse like structure on the top. Instead of the second story being missing it is actually a third story that seems to have been done at a later date that is gone if the orginal painting is to be believed.

The pavillion in the painting looks like it has a possible wing running off the left side with a truncated third floor (at least as far as the windows are concerned), what’s on the right is a taller wing or an entirely separate building, unfortunately obscured by the trees.

The author says the Duke of Richelieu “was not only a notorious libertine but a great general: during the Seven Years War he had driven the English out of Hanover” hence the name because of all the booty he made off with.

Donald –

You are right, the original Pavilion did have the cupola ‘penthouse’, as can be seen here, in this 1829 work by Christophe Civeton.

But the postcard I included in my post shows that this storey changed since then, the balustrade was moved upward, and the facade was altered to create a uniform exterior. It was that structure I was referring to. Indeed that top storey was not rebuilt in the park, and the remainder of the building was somewhat restored to its original design, except for it being symmetrical now, which it was not.

Good call, I did miss that first execution of the building.